Banned for Glory (part three)

(“Welcome back, my friends, to the show that never ends…” Except it does end, it ends here. I have no idea why I’m quoting Emerson, Lake and Palmer, but anyway… This is the third and final instalment of our in-depth look at the “golden age” of British film censorship. In part one we skipped through decades of stiff upper lip-style censorship to the swinging 60s before having a good old viddy at A Clockwork Orange, and in part two we travelled back to the mid-70s and wet the bed over The Exorcist, before bopping forth to the 1980s where we met the infamous Video Nasties that our mothers and fathers had warned us about. Following the introduction of the Video Recordings Act in 1984, there are more films banned in Britain than at any time in the past, and the BBFC reaches new heights in terms of power and influence. Their complete control over the release and distribution of films of many different stripes, from horror to hardcore porn, continues apace well into the 1990s. Surely it has to end somewhere? Read on to find out…)

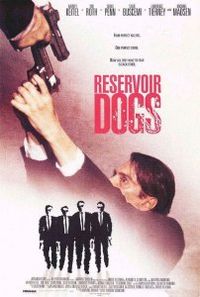

Reservoir Dogs (1992) – Yes, Reservoir Dogs. Easily one of the most celebrated, not to mention imitated, films of the last twenty years, Reservoir Dogs WAS banned in Britain, at least for a while. Despite a hugely successful (and record-breaking) cinema run, Quentin Tarantino’s seminal pulp homage to the heist movie met a similar fate to The Exorcist and was unavailable on home video in Britain for several long years (or maybe just a couple of long years) throughout the 1990s. This entire episode seems to be just about completely forgotten now, and indeed, a frustrating Google session heralded next to no information regarding the exact details of this ban. Rather, all I could find out was that there is now a video game (!) of Reservoir Dogs which itself is now banned… in Australia. But you can stick your new-fangled video games, cos its good old-fashioned video tapes that we’re interested in here, buddy.

As famous as Madonna and as instantly recognisable as the Mona Lisa, Reservoir Dogs is as iconic as a film can be. Indeed, so captivating it was at the time, that it became recognisable and iconic even to those of us who, thanks to the BBFC’s video ban, had yet to see it. I can remember a time in the early-to-mid-90s when no light-entertainment programme screened on British television was complete without some parody, pastiche or tribute to the film. From Noel Edmunds to Newman and Baddiel, they were all at it. The black suits and shades, the colour-coded aliases, and the hitherto long-forgotten 70s hits by Dutch crooners and Gerry Rafferty-of-Baker-Street-fame, use any of these references in a comedy skit, sketch or link and you were guaranteed a laugh of recognition from those who had seen it. For the rest of us, there was the peculiar experience of getting to know a film so well through comedy osmosis. Nowadays it is hard to imagine a single person in Christendom who hasn’t seen Reservoir Dogs, and as a result, I feel we have become a little bit blasé about it. So, to paraphrase the appeal once put to us by the good Dr. Kellogg regarding his Corn Flakes; have you forgotten how good it tastes?

Here are a selection of films I was enjoying circa-1992: Wayne’s World, California Man, Hudson Hawk, Meet the Applegates, The Hand That Rocks the Cradle, Cape Fear, Honeymoon in Vegas, Death Becomes Her, Unforgiven, Terminator 2, and Captain America (yes, the one with J.D. Salinger’s son in it. I loved it!). There’s some not bad stuff in there, and I was already into my horror films, but I NEEDED Reservoir Dogs to show me the way. I think we all did. A big part of the initial attraction was the fact that Reservoir Dogs was banned, of course. My obsession with The Exorcist was already several years old by this stage, and soon I would begin my quest for the Video Nasties. The difference was, however, that The Exorcist was from the olden days of the 1970s and the Video Nasties were banned way back in 1984, when I was but three-years-old. Reservoir Dogs was being banned right in front of my face and right at the same time that seemingly everybody in the world was raving about it. It was no secret why it had been banned, of course, everybody knew that. As Quentin Tarantino himself would later bemoan, Reservoir Dogs became almost universally known as “that film were the guy gets his ear cut off”. News reports feverishly detailing the allegedly high levels of violence and torture featured in the film would kick off a national debate on screen violence, the like of which had not been seen since the age of the Video Nasty. And, as is often the case, all this free publicity served to make those who hadn’t seen it want to see it all the more.

I first saw Reservoir Dogs on video while it was still banned on video. Unfortunately for me, this paradoxical scenario meant that the video in question was one of those filmed-in-the-back-of-the-cinema-with-a-camcorder jobbies that a friend’s brother had managed to procure (goodness knows what manner of terrorism he was funding!). Still, so desperate was I to see it that I didn’t complain and, despite the horrible sound and picture quality, people in front getting up to go to the toilet etc., I absolutely loved it. It was the summer of 1994, and I had never seen anything quite like Reservoir Dogs before. An intense, exciting and offbeat crime thriller, effortlessly cool and cleverly put together. It’s easy to forget just how astounding all that non-linear storytelling was the first time you saw it. And, as far as I’m concerned, a million and one lazy parodies will never diminish the unequivocal coolness of the opening slow-mo strut to The George Baker Selection’s ‘Little Green Bag’. Then there are the performances, from a crack team of then undervalued character actors and bit-part players, not one of whom would find themselves short of work ever again thanks to Reservoir Dogs, and each one of whom could supply a much lesser film with at least an iota of cool simply by association (astonishingly, the ear-slicer himself, Michael Madsen, would appear as the dad in Free Willy a year later). Of course, top-notch acting talent was absolutely essential in order to deliver Tarantino’s justifiably renowned dialogue, and my young friends and I set about learning it off by heart, returning to school that September full of tales of Madonna songs about big dicks, and having one’s penis glued to one’s stomach. They were our own twisted equivalent of the over-quoted Dead Parrot sketch of generations previous.

The dad from Free Willy, the bastard from Reservoir Dogs

But, was it as violent as the ladies and gentlemen of the press were making out? No, of course it wasn’t. I’m sure I’m not the only person who, after seeing Reservoir Dogs for the first time, couldn’t quite make out what all the fuss had been about violence-wise. Certainly, it’s a very bloody film, but not any more than a film with an 18 certificate has any right to be. And not any more than Sam Peckinpah’s ultra-bloody western The Wild Bunch, from over twenty years before, which I had already seen on TV by this time. How about the infamous ear-cutting scene? Obviously, no scene in which a man gets his ear cut off is ever going to be entirely pleasant, but the trick with this notorious scene, as with so many similar sequences in cinema history, is that you don’t actually see it taking place. Certainly, it’s a brutal and sleazy set-piece, but again, it’s not any more outrageous than what you’d expect to find in a film with an 18 certificate. And it’s also not any more outrageous than the “squeal like a pig for me, boy” male rape set-piece of John Boorman’s Deliverance, again from over twenty years before, which I had also already seen on TV by this time. But, sure enough, it was the hype surrounding the “ear scene” that led to Reservoir Dogs being denied a home video release in the UK at the height of its success. Unsurprisingly, the man behind that decision was James Ferman who, by 1992 had been in charge at the BBFC for nearly twenty years, and had famously condemned The Exorcist to a similar fate. Ironically, another director who had had one of his own films denied a UK video release by Ferman and the BBFC was to unnecessarily and rather childishly add to the hype by walking out of a Cannes screening of Reservoir Dogs during the ear-cutting scene. That director was Wes Craven, and anyone who has ever sat through his The Last House on the Left (one of the nastiest of all the Video Nasties) is entitled to ask; what the hell was his problem?

By 1994 the name Quentin Tarantino was a universally accepted byword for both violence and cool. In addition to his own Reservoir Dogs, another film was responsible for attaching the former, and perhaps less welcome, tag to his name. Natural Born Killers wasn’t directed by Quentin Tarantino (it was directed by another explosive talent, Oliver Stone, on one of his regular off-days), nor was it even written by him. In fact, Natural Born Killers was merely based on a screenplay written by Quentin Tarantino, but it is a testament to the level of both his fame and notoriety at the time that the film was sold under his name, and that the tsunami of controversy it attracted was propelled in his direction. The most controversial film of its era and the centrepiece of the debate on screen violence at the time, Natural Born Killers hit the headlines in this country after it was accused of inspiring several copycat killings in America. Many accused the film of glamorising violence, and the extent to which said glamorisation could potentially damage society was fought over louder and harder than at any time since the release of A Clockwork Orange in the early 1970s. The buzzword of the era was “gratuitous”, and all of a sudden films were assessed for scenes depicting gratuitous violent content; content intent solely on shock and exploitation, and superfluous to the plot. The trouble was that to some all screen violence by its very nature is gratuitous, but then others still are made of stronger stuff and can tolerate higher levels of violence in films and television programmes. How then can you possibly decide what is gratuitous and what isn’t? It was the question that would define the decade in terms of censorship, and whoever could answer it loudest and most convincingly would determine the future of British film censorship into the new millennium.

Meanwhile, back in the mid-90s, Natural Born Killers enjoyed a successful, if obviously very controversial, cinema run in the UK, but would find itself banned on video in the British Isles following the Dunblane massacre of 1996. The film was not thought to be connected to the killings in any way, but the release on video of a major Hollywood film bearing such a title and featuring such explicit content was thought to be just too much in the aftermath of such a terrible tragedy. I was as eager to see Natural Born Killers as I had been to see Reservoir Dogs. It didn’t matter that Quentin Tarantino hadn’t actually directed it himself as at that point I would lap up anything that was even vaguely connected to the generously chinned, notoriously verbose film nerd. More often than not this could be a painful experience, as anyone who has sat through True Romance (what do you mean it’s actually quite popular?) or Crimson Tide (he had a hand in writing both of them) can attest. From Dusk till Dawn (in which he starred) isn’t much better. So it was to be with Natural Born Killers, and despite the whole Tarantino-Oliver Stone connection, NBK, as it is often annoyingly abbreviated to, is the absolute pits. Pushing aside the whole violence debate for a moment, the film is little more than a flashy, vacuous, sorry mess which disappears up its own “MTV Generation” bumhole before the first 15 minutes are even up. It was a waste of everybody who made it’s time, and it was a waste of my time too, when I eventually got to see it.

Quentin Tarantino, the handsome devil

However, as should already be clear, I still really like Reservoir Dogs. In fact, I still really like Quentin Tarantino. As I was saying earlier, when Reservoir Dogs arrived on the scene in 1992, I had never seen anything like it, and both the film and its director helped lead me away from the sort of mediocre mainstream fodder I was enjoying as a young adolescent and get me into more sophisticated stuff. Even though I couldn’t actually buy or rent a copy of Reservoir Dogs at the time, I could buy a biography of Quentin Tarantino (he was an absolute megastar back in the day) and find out about other great films that way. My already nascent interest in the likes of Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola was encouraged, and through Tarantino I learnt about loads more great films I had to look out for, many of which were sometimes screened on British television and many of which I would have otherwise missed (Breathless, Jim McBride’s swaggering American remake of Godard’s A Bout de Souffle, and the Reservoir Dogs-inspiring gangster drama Pope of Greenwich Village, to name but two). And, of course, Quentin’s own films were great, as well. Pulp Fiction arrived in 1994, and managed to be even more phenomenally successfully, effortlessly cool, and fantastically inspired than its predecessor. Better yet, it would pass the censors with minimal trouble (although James Ferman later expressed regret over not cutting John Travolta’s “shooting up” scene, describing it as an “advert for heroin”), and I could see it on video the following year (I was too young to see it in the cinema, although I remember my sister going and being really confused by the whole non-linear storyline thing. “John Travolta dies in it, but then he comes back to life at the end”, was her interpretation of events at the time). I’ve probably seen Pulp Fiction more times than any other film, largely due to the period I watched it almost every day in early 1996. Quentin Tarantino was the first film director I loved in the same way one might love a rock group or footballer, and because of this I’ve continued to follow his career closely. His next film up was Jackie Brown in 1997, which may have seemed like a bit of a damp squib to many, but I can assure you is every bit as good as his first two films, and is my personal favourite of his (a crime caper as moving as it is riveting. No other hotshot Hollywood brat would dare follow up the biggest hit of their career with a film centred around a lonely, 40-something black air stewardess, played by a relatively obscure, long-forgotten blaxploitation icon). Jackie Brown is as close as he’s ever come to eschewing the “conventional” crime genre and his trademark pulp references and aesthetic, to some extent at least, in favour of something more personal and intelligent. His latest efforts (Kill Bill Pts. 1 & 2, Death Proof) may have thundered off in completely the opposite direction to Jackie Brown in terms of depth and feeling, but he’s a still a popular filmmaker to be treasured. Ignore floppy-haired indie fops who sidle up to you at parties and say “Oh, but Kill Bill is just made up of bits of other films that he’s ripped off!” They probably haven’t even seen Kill Bill, and they certainly haven’t seen any of the films it apparently “rips-off” (they read about them in The Guardian, who are also just showing off). Kill Bill, and all of Quentin Tarantino’s films, reference (being the operative word, as opposed to rip-off) a host of other films and genres, but that’s because Quentin Tarantino loves films. He’s studied films his whole life and capturing the essence of a genre, distilling the flavour of an entire cinematic era is one of the things he does best. It is one of the things all great modern directors do best; Martin Scorsese references Michael Powell and Quentin Tarantino references Martin Scorsese. The idea that if you presented evidence of the films he’s supposedly pilfered from to Tarantino himself that he would shrink away in exposed shame is utterly laughable. He would be the first to admit his influences because, again, the man loves films. And in an era where the majority of directors working in mainstream cinema are seemingly either coked-up music video graduates or sad-sack comic book aficionados, a successful film director whose first love and primary interest is film is, strangely and sadly, increasingly a rarity.

Reservoir Dogs and Natural Born Killers are both now freely available on video (and DVD), of course. Indeed, these days they are both regularly screened on UK terrestrial television, and nobody bats an eyelid. And it’s not just them, neither. The majority of films once banned or heavily censored in this country are now also freely available on multiple formats from numerous outlets, and the growth of multi-channel television has even allowed a one-time cinematic pariah of the stature of I Spit on Your Grave a chance to grace the British airwaves. So, what the hell happened?

James Ferman

The simple answer might possibly be this; James Ferman retired as the chief executive of the BBFC. Whilst not the definitive answer (if it were, it would suggest that Ferman had been some kind of Stalinist, all-powerful film dictator, which he most certainly wasn’t), it does stand up to considerable scrutiny, especially when one observes the tide-change that occurred in British film censorship following his retirement, in 1999. Ferman’s legacy is a muddled one, but that is somewhat suitable when one considers what a complex character he was (he passed away in 2002). Often cast as an out and out bogeyman and reactionary (he is chiefly remembered as the man who banned The Exorcist for over twenty years), Ferman was also derided in some circles as weak-willed and overly liberal. The counterpoint to his banning of The Exorcist was perhaps his decision to pass David Cronenberg’s heady mix of violence and eroticism, Crash, completely uncut in 1996. The truth, as I see it, is that Ferman was both; a liberal and a reactionary. And, if you ask me, that’s exactly what an assured and effective film censor should be.

There was a time, largely when I was a teenager, when I believed that all forms of censorship were inherently wrong. No one has the right to tell others what they can and can’t watch, freedom of speech maaan, I thought. These days I believe in sensible and considered censorship to a degree, and I have come to recognise James Ferman as a pioneer of this school of thought. Oh, don’t get me wrong, Ferman has a number of blots in his copybook, perhaps above all else the whole Video Nasty debacle. But many of his decisions were measured and intelligent, and he approached the task in hand psychologically as well as morally. Previous BBFC chiefs had seemingly made their decisions on a purely black and white basis (was a film too violent or wasn’t it?), but Ferman wasn’t afraid to think outside the box. Some of the conclusions he reached were a little odd, a prime example being his decision to lumber Stanley Kubrick’s Vietnam odyssey Full Metal Jacket with an 18 certificate. The sticking point was that Oliver Stone’s similarly-themed Platoon, which was no less violent, had been granted a 15 certificate. Ferman’s reasoning? Oliver Stone had personally fought in Vietnam whilst Stanley Kubrick hadn’t. Therefore the violence in Stone’s film was based on actual life experience, whereas Kubrick’s was a fiction and thus harder to validate.

Whatever you think of that decision, and I’m not so sure myself, you can’t deny that James Ferman was right in his desire to bring a more logical approach to film censorship. An example of a Ferman decision that displays more in the way of sound pragmatic thought was his refusal to cut the term “penis-breath” from Steven Spielberg’s E.T. Ferman was of the opinion, correctly as it turns out, that it was a term of abuse too obscure for children to pick up on, and it could be left in the film without any worry. Like that other long-serving BBFC head honcho, John Trevelyan, Ferman could boast considerable influence in major Hollywood circles, and although he was often perceived as a schmoozer, he wasn’t afraid to rein in the likes of Spielberg, demanding cuts be made to the wildly popular Indiana Jones films, which he considered a touch too violent for children. Perhaps surprisingly, one of the films to receive the most attention during Ferman’s reign was Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves. A much more considerable than it might at first sound 28 seconds was shorn of this supposedly family-friendly adventure romp, most of which taking place in the grisly opening sequences (a blinding and a hand amputation). I can’t help but feel sympathetic to Ferman in his fight against major studio films which set out to have their cake and eat it. If you want your film to have a U rating, it should look like a U rated film, you can’t sneak in unsuitable content and hope to keep a more lucrative rating (films with a lower rating generally stand to make a higher gross).

Fuck me, I love old VCRs

Family films are one thing, but what of films that were never intended for mass consumption? As discussed in the second instalment of Banned for Glory, James Ferman was the head of the BBFC during the Video Nasty outrage, and thus can be considered the key player in the full blanket banning of 39 films of violent, and “potentially damaging”, content. Along with his long-standing and stubborn refusal to grant The Exorcist a release on UK home video, the Video Nasty episode is what Ferman is most famous for, and many think of him in the same light as rabid moralists like Mary Whitehouse, or unscrupulous scapegoat-seekers like Margaret Thatcher, due to his involvement in it. I think this is unfair. With exciting images and media of many varieties leaping out at us from all four corners of our living rooms in this day and age, it’s easy to forget just what a blistering new concept home video was when it first appeared in the late 70s. And when the BBFC were at last granted the power to control it in 1984, they had to consider the influence that a vast new number of films could weld in the home for the very first time. History may have shown that Ferman’s decision to ban The Exorcist in the home on the grounds that it could be used as a tool to frighten and psychologically torment young children was perhaps later proven unfounded, but it was a sensitive and sincere decision nevertheless, so we should cut the man some flack. The destructive potential of home video was at the time unchecked, and I can’t help but feel that Ferman made a safe, but essentially justifiable decision. With the Video Nasties he, and the BBFC, took a more scatter-shot and perhaps less easily justified approach. It did seem that the board were bowing to pressure from certain moral groups and at least several films on the list really didn’t deserve to be there. These weren’t mainstream films after all, they weren’t made with a family, or even general, audience in mind, and so long as the owner of the video cassette in question was responsible with regards as to who could access it then there shouldn’t be a problem. For the more troublesome films on the list, especially the handful depicting real animal cruelty, perhaps a full ban was the best thing. Censorship is always a difficult issue, and especially when dealing with the censorship issues surrounding a nascent and unfamiliar technology, difficult and unpopular decisions have to be made.

It is also somewhat unfair that James Ferman is chiefly remembered as a “banner” of things, when several films were saved from censored limbo during his time at the head of the BBFC. Indeed, many Video Nasties did not languish in illicit unavailability for long, with the board reappraising many under Ferman’s duress. The first film out of the traps was Joe D’Amato’s Absurd, a loose sequel to his earlier Anthropophagus The Beast (which remained firmly on the list, in all it’s foetus-munching glory). Absurd was considered passable on second thoughts and little more than a blatant rip-off of John Carpenter’s Halloween. Three minutes of more unsavoury footage were cut in 1983, the very same year the Video Nasties list was first drawn up, and Absurd was sent on its way. A few more titles escaped their bans following a retrial throughout the 80s and early 90s, most notably Tobe Hooper’s The Funhouse and Dario Argento’s Inferno, a pair of excellent, intelligent horror films from two of the genre’s biggest names. Several American slasher films were also deemed tame enough for a video release under Ferman and notably the Canadian effort Visiting Hours (starring William Shatner. Oh, yes) was screened on ITV a few years after being removed from the list, making it the first Video Nasty graduate to air on UK television. Most of the list would remain banned until after Ferman’s retirement, however, but outside of the Video Nasties he would eventually pass a small handful of notorious films, including Straw Dogs and Roger Corman’s possibly pro-LSD, freak-out fest The Trip. Without question, however, of all the things Ferman was to un-ban during his reign, the decision to make hardcore pornography legal in Britain was the one that made the largest and deepest impact (I just read the end of that sentence back. Hello Freud!). It’s staggering to think that hardcore pornographic films and literature were totally illegal in the UK until 2000, but it was James Ferman who finally decided that we were all big enough and ugly enough to be allowed to watch consenting adults rutting like mad animals in the comfort of our own homes, just in time for the new millennium (not literally rutting IN our own homes, unless you happen to be one of those “sex people”). The ban was not fully lifted until after Ferman had resigned, but it was he who set the wheels in motion, and the biggest decision he undertook in his tenure was also his last.

Some hardcore porn. Yesterday.

I don’t think we need go into any more detail regarding hardcore porn. We’re really not that kind of website. We will however take a look at what happened at the BBFC post-Ferman. You may remember my attempt to inject a bit of perspective into proceedings by casting each BBFC chief as a British prime minister based on a combination of their perceived personal attributes, the success of their tenure and the era in which they operated. Thus suave, swinging and successful John Trevelyan was Harold Wilson. Well-meaning, but ultimately unsure and unsuccessful Stephen Murphy was a composite of Ted Heath and Jim Callaghan, and the dominant, dominating, self-promoter, and self-appointed moral philosopher and friend to the stars James Ferman was Margaret Thatcher AND Tony Blair (which sheds a little light in both directions, if you ask me). So then, does that make Robin Duval, Ferman’s successor, a dour, pragmatic, kicking-against-the-pricks Gordon Brown-type? To be honest, I have no idea. What I know about Robin Duval, I could scarcely write on the back of a postage stamp. He only stayed in the job until 2004, before being replaced by David Cooke, who remains in charge to this day, and who I also know nothing about. Perhaps by design, Duval and Cooke have never attracted the fame and notoriety that their predecessors “enjoyed”, and holding the very top job in British film censorship doesn’t seem to be quite the high-profile, occasionally poisonous position it once was. While those before them seemed to have a very specific brief each tried to work to in their tenure (Trevelyan; relax and modernise. Murphy; please everyone. Ferman; ban loads of stuff, attempt to explain why), Duval and Cooke seem to have been happy just to pass almost anything but the uttermost beyond of the uttermost pale. The answer to the big censorship question of the 90s seems to have arrived; what is gratuitous? Not much, only the really, really bad shit! Please remember that while the BBFC of old flipped their wigs over Marlon Brando bonking like mad without even taking his trousers off in Last Tango in Paris, the BBFC today will let you watch tedious indie actors authentically penetrating each other in guff like Nine Songs and The Brown Bunny, all in the name of art! The bar has truly been raised, and you’re going to have to really go out of your way if you want to upset the new-look BBFC. If wild ‘n’ raunchy modern cinema was deemed acceptable by the censors, then surely it would only be a matter of time before some older controversial films were re-submitted by opportunistic distributors keen to latch onto the spirit de change.

The two big-hitters that burst open the floodgates were The Exorcist and A Clockwork Orange. For so long James Ferman’s personal bete noire, The Exorcist became a massive mainstream cultural phenomenon once more after Warner Bros. had a flashy new print passed for a general cinema release in 1999. The newly-retired Ferman wasn’t around to fend it off, and one suspects that he must have been inwardly fuming when he caught wind of Duval’s decision to finally unleash the film uncut on video (and newly arrived DVD) the very same year. As we learned in part one of Banned for Glory, A Clockwork Orange re-emerged in 1999, also. And, yes pedants, Stanley Kubrick’s seminal, glam-era rumination on violence and punishment was never actually banned by the BBFC, but I tell ye, it was the BBFC sniffing around it at the behest of Home Secretary Reginald Maudling in the aftermath of it’s highly controversial initial (uncut) release in the early 70s, that could, as much as anything, have caused Big Stan to have withdrawn it himself. Anyway, these two long unseen titans of tabloid tittle-tattle and terror being released to little more than a loud chorus of gratified enthusiasm perhaps set the precedent for the BBFC’s post-Ferman policy; release (almost) everything! From 2000 onwards almost every Video Nasty found its way onto video (and now DVD) in the UK for the first time since the introduction of the Video Recordings Act in 1984. From the most notorious; The Evil Dead (passed in 2001), The Driller Killer (2002), Zombie Flesh Eaters (2005). To the more obscure; Night of the Bloody Apes (passed in 1999) in which a gorilla-to-human heart transplant goes horribly wrong, perhaps unsurprisingly. Prisoner of the Cannibal God (2001), a rum little number which, rather amazingly, stars Stacy Keach and Ursula Andress, and the notoriously awful Don’t Go in the Woods (2007), which I’ve not seen, but which is apparently the most laughably amateurish Video Nasty of ‘em all, and therefore possibly the most laughably amateurish film ever made. A fair number of the Video Nasties that do get re-released are still heavily cut, with Cannibal Holocaust and I Spit On Your Grave (both passed in 2001) rather predictably receiving the heaviest scissor treatment. Indeed, if there are two things that the BBFC have retained immense disapproval of, it’s the depiction of animal cruelty (real or otherwise) and sexual violence. A sizeable number of Video Nasties just so happen to contain either animal cruelty (particularly any film with the word “cannibal” in the title) or sexual violence (particularly films belonging to the “rape-revenge” subgenre, such as I Spit On Your Grave). Some even manage to contain both, and rather head-spinningly, Island of Death, an immensely sleazy Greek serial killer romp, boasts a scene which combines both these taboos at the same time, as the main protagonist proceeds to rape a goat at one point in the action! However, the BBFC seem happy enough these days to cut anything they consider too extreme, or “gratuitous”, and pass the rest of the film, with even Island of Death getting a release in 2002, after being shorn of its goat scene. I “kid” ye not!

The poster for SS Experiment Camp. Provocative? Not a bit of it

The retrial and reappraisal of Video Nasties is an ongoing project at the BBFC, with the most recent additions to the ever-growing re-released list being Wes Craven’s notoriously violent take on Bergman’s The Virgin Spring, The Last House on the Left (passed uncut in March last year), and the legendary, fabulously named Jesus Franco’s fabulously titled Sexo Canibal (passed under it’s boring UK title, Devil Hunter, just two months ago). As it currently stands, only 11 of the 39 Video Nasties successfully prosecuted in 1984 remain banned to this day. Several of these, it would seem, only really remain “banned” because they are so staggeringly shoddy and inept that no distributors in their right minds would be foolhardy enough to believe they could make a profit by attempting to sell them to the British public. This pack is lead by infamous hack Andy Milligan’s loony costume slasher Blood Rites (touched on in Banned for Glory part two), and unless scenes of astoundingly amateurish filmmaking should be banned (I believe they should in fact be encouraged), it could surely be passed with only a few minor cuts. Likewise three more titles which remain banned; Forest of Fear, Frozen Scream, and Mardi Gras Massacre, each one an American production, and dealing with zombies, mad scientists and serial killers, respectively. Spain chips in with The Werewolf and the Yeti, which unsurprisingly but bizarrely appears to be about both a werewolf and a yeti. I’ve not seen any of those films, but by all accounts they are truly awful and merely comparatively tame. If anyone’s got the time and money to start a DVD company, that’s five potential smash hit titles we could put out right there, after simply re-submitting them for classification to the BBFC, of course. Of the six Nasties left, three belong to surely the most reprehensible and loathsome subgenre of them all, the Nazi exploitation picture, or “Nazisploitation”. These films are so wrong on so many different levels, I feel rather unclean just writing about them. For anyone lucky enough to be uninitiated with this truly bottom-of-several-barrels shit, these films contain little other than continuous displays of torture (frequently sexual, sometimes otherwise; always revolting and offensive) largely directed at the female inmates of Nazi concentration and POW camps. The Video “Nazis” (if you will) that remain banned to this day are; The Beast in Heat, Gestapo’s Last Orgy, and Love Camp 7. I haven’t seen any of these films, nor do I want to, and nor will I ever endeavour to endure them under any circumstances. I was going to say I would cast serious dispersions on anyone who would want to see them, but as they generally boast production values disgraceful enough to match the “dramatic” content, I appreciate that they attract their share of adventurous schlock fans. I’m afraid throwing Nazis and concentration camps into the mix takes it just a step too far for me. Strangely enough, the most infamous example of the genre, SS Experiment Camp, was passed in 2005 after it was deigned ludicrous, but not completely sickening nor totally morally void. I have seen a bit of it (years ago), and remember little other than some wholly inappropriate soft-core sex (consensual), and the immortal line “What have you done to my balls, you bastard?!” spoken by an irate SS officer after he himself runs afoul of a particularly nasty experiment. Another famous example of the genre, Ilsa, She Wolf of the SS, was also banned by the BBFC, but never found its way onto the Video Nasties list. And lest you assume that them there Italians are behind all this sordid squalor (although you’d be largely correct), that last feature is an American production.

That leaves just three more still forbidden Video Nasties for us to meet. Easily the most interesting remaining case is the curious Nightmare Maker. Universally acclaimed by everyone who has seen it, this apparently highly atypical American slasher has been described variously as a demented soap opera, a scalp-tinglingly intense psychodrama, and a tongue-in-cheek serving of suburban Grand Guignol. Veteran wild card Susan Tyrrell (Fat City, Forbidden Zone) reportedly devours the scenery as a maniacal, obsessive aunt who will stop at nothing (absolutely nothing!) to keep her orphaned nephew by her side, and ultimately she hopes, in her bed. After her young charge catches her repeatedly driving a carving knife into the neck of a TV repair man, a racist, sexist, homophobic and quite possibly mental police detective (played by Swedish hard-case and Tarantino favourite, Bo Svensson) turns up and begins to uncover all kinds of weirdness and lies. Nightmare Maker does sound like one heck of an interesting trip, but sadly I am yet to see it as it is still technically banned, no foreign DVD release has ever appeared, and I’ve never managed to locate a copy on pre-cert VHS. It was, however, re-submitted to the BBFC for a second time in 1987, and rejected again. It has not been re-submitted since, despite developing a not inconsiderable and potentially lucrative following of would-be fans, thanks in no small part to the high praise heaped on it by those who have seen it. These lucky few also seem to agree that while Nightmare Maker is not for the faint-hearted, it is also not an overly unsettling or gruesome film, and thus should really have been passed by the BBFC by now. Perhaps the censors have deemed the incestuous, psychopathic feelings of the Tyrrell character as a touch too much, but if they were to pass it, and a distributor were to pick it up, it’s safe to assume we’d be treated to one of the most complex and interesting of the Video Nasties.

Still banned after all these years; Nightmare Maker

Complex and interesting aren’t words you can attribute to our remaining two Nasties that have yet to be un-banned in this country. Generally offering little more than squalid titillation, women-in-prison films failed to even come close to making as large an impact on the list as those other 70s staples, the cannibal-themed “Mondo” movies and Nazisploitation, with imprisoned ladies boasting a paltry one entry. Still, you can trust our old friend Jesus Franco to lower the tone, and his Women Behind Bars sees him subjecting his own actress wife to some explicit onscreen torture. Another of Franco’s efforts in the same field, Women in Cellblock 9, never showed up on the list, but remains firmly banned by the BBFC to this day following controversial queries regarding the ages of some of the actresses involved. The old rape-revenge template chalks up another entry, however, as the last of the 11 Video Nasties that remain banned in this country is the odious racial variant on Last House on the Left, Fight For Your Life. Concerning the racial abuse and torture of a black family at the hands of white thugs, it is absolutely no surprise that Fight For Your Life is still banned in this country and it will probably remain so until hell itself freezes over. Mind you, that’s what I used to confidently predict about many of the other films on the list, particularly the likes of I Spit On Your Grave and Cannibal Holocaust, but nowadays you can pick up a copy of either of those in your local HMV. Anyway, if you really want to see Fight For Your Life, it’s only a couple of mouse-clicks away. The twin developments of the internet and multi-region DVDs have completely undermined the power of a lot of the BBFC’s decisions in this country, and if a film is freely available on DVD in America, as Fight For Your Life and almost all of the Nazisploitation films are, a simple trip to Amazon or eBay will set you up with a copy, and it’s all perfectly legal.

And that, I believe, is pretty much where we came in. When I first developed an interest in films that were banned, beginning with The Exorcist, continuing apace with A Clockwork Orange and Reservoir Dogs, and developing into a full-blown obsession with the Video Nasties, I was shocked, awed and enraptured by the very notion that there were some films so mad, bad and dangerous that you were forbidden by law to see them. Nowadays, I can’t help but feel something has been lost by the fact that there are no real banned films anymore, that there are no infamous, outlawed celluloid nightmares worth tracking down. Aside from the 11 Video Nasties that remain banned (and Nightmare Maker is the only one apparently not racist, Nazi or downright bad enough to be worth seeking out), the list of films still banned in this country is a rather unappealing one consisting of little other than immensely dubious and sickeningly perverse hardcore pornography, that I really hope no one would want to see anyway. The relatively few proper, non-Video Nasty films that remain banned include several similar shockers that never made it on to video, such as Ilsa and Cellblock 9. A couple of interesting examples besides are the 80s American slasher, Silent Night, Deadly Night (with the BBFC refusing to unleash a bloody, if generic, horror film in which the killer wears a Santa costume for fear of psychologically buggering children everywhere), and Mikey, an unsettling yarn concerning a murderous infant that was banned in the wake of the James Bulger murder case (the film that attracted the largest media scrutiny in the wake of the case, tired killer doll sequel Child’s Play 3, was never banned, even if many video outlets stopped stocking it. These days it plays regularly on ITV2 without attracting any attention). The days when the BBFC welded enough power to keep a massive studio smash like The Exorcist off our screens seem like an age away now, when in reality it is only just coming up on a decade. A decade of massive change it has been, and although I can’t deny it is a great thing that a film as good as The Evil Dead, say, is now widely available minus the fuss and bother of pirates and bootleggers, I also think that the acceleration of freedom has been implanted a tad too fast and a touch too recklessly.

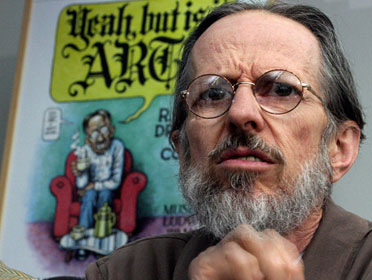

The Great Robert Crumb – A surprising candidate for the next head of the BBFC?

Not only has the exciting and fractionally dangerous (in my mind, at least) challenge of tracking down a genuinely banned film been lost, but the mainstream media has become oversaturated with genuinely startling nastiness, and there doesn’t seem to be anyone willing or able to keep it in check. Oh, don’t get me wrong, I’m writing this as a confirmed horror nut, and someone who has seen some badass beyond the pale bullshit in over 15 years of film viewing (and rather enjoyed it, on occasion), but when it comes to censorship I am very much a subscriber to the belief “Everything’s not for everybody”, as the legendary artist Robert Crumb put it when opining the fact his pre-teen daughter had been upset by the violence in Goodfellas. It just seems to me that there was something to be said about having to track down incredibly violent and outrageous films for yourself. For one thing, the limited availability of these films kept the numbers watching them down to the committed view. Secondly, if you went looking for a certain film it was generally something you were interested in, had read up on, and were prepared for. I just can’t get my head around someone wandering into any old multiplex or Blockbuster around the corner and catching a film as sickeningly violent, morbidly cynical and grimly salacious as Hostel or Saw. I remember being slightly unsettled by a chap in my office at work once recounting several of the glossy, gut-wrenching atrocities he had seen enacted in Saw 28, or whatever, in the Odeon the night before. He was the sort of person who normally only went to see films with Will Ferrell in them, and while there is some truth in the fact that if you’re not a horror fan you shouldn’t see a horror film, the poor fellow had still been clearly disturbed by a film that could rival almost any of the original Video Nasties in terms of nastiness. The only difference is he saw it pretty much accidentally, he didn’t hike 20-odd miles to some random car boot sale to buy a copy of it. Even people who aren’t necessarily upset by this sort of fare are a worry, and while I acknowledge that to be influenced and inspired by screen violence one must possess violent tendencies already, do we really want such overly sadistic films to be so freely available? The increasingly sleazy brutality of modern mainstream horror films has been a cause of much alarm to me in recent years. As much as anything, it is the fact that their popularity suggests how jaded people have become to any trace of traditional horror filmmaking, that a ghoul or monster will get laughed off the screen, and only rank torture can carry any water, or indeed, blood. One also can’t help but be shocked by the levels of xenophobia and misogyny displayed in these films, particularly the Hostel series and the Brazil-set, tourist traumatising torture porn-fest Paradise Lost (evidently not based on John Milton’s epic poem). If things continue this way, very soon all modern horror films will resemble a remake of Fight For Your Life filtered through a Slipknot video, with an ex-Guantanamo bay state-paid torturer working as an on-set consultant.

In conclusion, I suppose I’m appealing for two things here; one, better modern horror films please, although that is something of a side issue. Two, let’s have more in the way of sensible censorship these days. It’s great that we have a largely free media (in some respects, at any rate), but we need organisations like the BBFC to keep things in check. I’m not going to go all “in my day” on you, but we all know that violence is an ongoing problem in our society today, and we cannot allow money-hungry mainstream film companies to continue to pump sordid, sadistic films onto our screens and expect to go on unregulated. I think the age certificate system is great, but in certain cases we’re going to need a bit more. Either good old-fashioned heavy cuts or, I don’t know… A psychological survey and personality test to be filled in before admittance can be granted? If that sounds a bit fascist, then ask the BBFC for a better answer. They get paid to come up with this stuff! I just don’t think they should be afraid to weld a bit of power every now and then if they deem it necessary. I realise this isn’t a fashionable opinion, but let’s not forget; everything’s not for everybody.

Sorry if I got a bit lofty and moralistic at the end there, but I hope you enjoyed my semi-autobiographical, somewhat epic journey through the recent history of British film censorship. And I hope it managed to resonate with at least a few people who, like me, still can’t quite get over the fact that just under ten years ago there were shit loads of really great (and shit loads of really not so great) films banned in this country, and were actually rather pleased, intrigued and excited that there were.

Now, if you’ll excuse me, I’m off to see if I can track down an old pre-cert VHS copy of Nightmare Maker, before that turns up in HMV an’ all. Cheerio!