Ode to Moviedrome | DaysAreNumbers

Or: How I learned to love incredibly strange films cos my mum allowed me to have a TV in my bedroom

I don’t know about you, but at my school there was an unofficial clique, a group of kids who were allowed to watch television long past what should have been their bedtime. They either, like me, had a TV in their bedroom (Hey! I paid for it myself. I had a paper round, you know) or, stranger yet, they had the run of their house after dark, probably because they had elderly or alcoholic parents. This little group, it was never spoken of by name, would gleefully, if unceremoniously, convene on a Monday morning (or occasionally during the week) to recount what strange and startling films they had seen on late-night telly. Often a bit of violence or nudity would be enough to create a major talking point, but occasionally a film so bizarre would have made an appearance that when it was brought up in conversation, we would adopt the air of men (or pubescent boys) who knew that we had each been changed by what we saw, and the world could never appear the same again.

I cherish these memories of illicit television viewing and the more I think about it, the more I have come to realise that the 1990s must have been a golden age for films on TV, and one that seemingly can never be repeated. It was an era when Britain’s stringent censorship laws were finally being relaxed and previously maligned and derided genre fare (low-budget horror and sci-fi, imported westerns, exploitation) was being reassessed by critics, with the choice cuts heralded as neglected gems. This spirit of reform and reappraisal is personified in my mind by BBC2′s seminal Moviedrome series, which appeared in two incarnations between 1988 and 2000. Moviedrome was a late-night film showcase, which routinely began with an informative introduction by its presenter, originally director Alex Cox, later journalist Mark Cousins. The brief was that it would show mainly (though not exclusively) lower rung, lower budget films that were often brilliant, always at least a little bonkers, and certainly unforgettable. Many films that are now casually recognised by many as bona fide classics received their UK television premiers on the series, and it quickly became essential viewing for all fanatical film fans and cult connoisseurs. Moviedrome truly was the terrestrial home of the weird and wonderful, and if I was too young to fully appreciate it in its early run, I was more than ready for it when it reappeared in 1997.

Below is a list of six jaw dropping films which I managed to catch, mostly by happy accident, on late-night terrestrial television throughout the 1990s. Each remains a firm favourite to this day, and each undoubtedly has helped lead me to where I am today, which is writing about them on the internet, rather than being outside enjoying myself or earning lots of money as a lawyer or something. Not all of them were broadcast on Moviedrome; in fact, only three were, two were on BBC2′s Forbidden Weekend, and one is from another BBC2 season, the confusingly, similarly titled Forbidden Season.

So please, sit back and help yourself to a little nibble of some of the finest cinematic contraband a license fee can buy. Just remember to keep the noise down, and don’t forget to position your finger on the off button in case your mum comes in.

Â

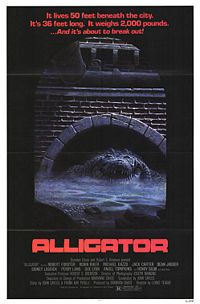

Performance (1970)

Appearing on Moviedrome a year after Performance, this wild and witty monster movie chews up taboos with as much relish as its titular beast chews up innocent (and some not-so-innocent) victims. Easily the best of the Jaws imitators, and I’m going to stick my neck out (or maybe stick my head in? Stick my head in an alligator’s mouth? No? Forget it) by saying I like it almost as much, which is truly testament to how great Alligator is.

The film begins with an irate mother flushing a baby alligator down a toilet, unbeknownst to its adolescent owner. We then fast forward a few years to discover that this same baby alligator has mutated into a terrifying monster by feasting on the dumped corpses of genetically messed about with dogs. It then embarks on a change of diet to befit its massive size, and when sewer workers start disappearing, crumpled cop Robert Forster (later rescued from the wilderness by Tarantino for Jackie Brown) is called in to crack the case. No one believes him when he cries alligator, of course, and the unscrupulous tycoon behind the dead dogs orders a cover up. However, when the ravenous reptile breaks out onto the streets, no one, and I do mean no one, is safe.

It is no accident that Alligator is so brilliant, it was after all scripted by American Indie elder statesman John Sayles, back when he was on a roll as a horror scribe (he also penned the similar Piranha and The Howling, both for Joe Dante). It has to be the cleverest creature feature ever made and, as well as delivering a not inconsiderable eco message, it also has fun dealing with cliché and crafty coincidence. Remarkably, the childhood owner of the alligator is now a top scientist trying to stop it in its tracks. Remark-abler still, the greedy gator is presented with an opportunity to put the shady tycoon responsible for its mutation on the menu. Forster’s world weary cop routine is a joy, and the show is almost stolen by Manchurian Candidate star (or Ghost Dog’s hip-hop spouting Mafiosi to you Jarmusch fans) Henry Silva as a pompous big game hunter drawn to the big city for the big kill.

Alligator really astounded me at the time, however, for its aforementioned disregard for taboo. Even in the nasty old 80s, you could always rely on mainstream horror not to go too far, and that the old Spielberg cliché of never harming the child would be followed. Not so with Alligator as children are chomped, and almost an entire wedding party is devoured alive with unflinching relish. A scene in which the alligator snaffles a baby is scrapped in most cuts of the film to this day.

Alligator, incidentally, played on Moviedrome as a double bill with the overlooked Larry Cohen’s mystical take on the monster movie, Q – The Winged Serpent. I was a bit too young for the subtleties of Q, and promptly fell asleep. Having seen it since, however, I can recommend it as highly as Alligator, and can think of no double bill with quite as much bite.

Â

Bad Taste (1987)Â

It’s amazing to think that the director of such a gloriously gory, superbly slapstick film as Bad Taste would later be invited to helm cinema’s second most successful trilogy (you know the one I mean), and it’s kind of sad that that’s where Peter Jackson ended up, because I can’t help but feel we’ve been deprived of more of the same witty, resourceful low-budget schlock that he would presumably have continued to make otherwise (there was word of a Bad Taste sequel for some time). He coulda been the Kiwi Corman!

Bad Taste starts out with the brilliant premise that evil aliens with a taste for human flesh have landed in New Zealand to harvest earthlings for their intergalactic fast food franchise. Called in to put an end to this extra terrestrial terror are the wonderfully named Astro Investigation and Defense Service (geddit?), who are apparently just as prone to causing messy blood â?n’ guts-shed as their alien opponents. And if that’s what you’re looking for, then you’ve come to the right place.

And that’s certainly what I was looking for the first time I saw Bad Taste, showing as part of BBC2′s Forbidden Weekend in 1995 (a season of previously banned or censored films, more on which later). I was staying over at my mate Neil’s house (lads can have sleepovers too, right?) and while initially savoring the prospect of watching what was being heralded as the goriest film ever to be shown on British television, it wasn’t long before we realised what a laugh Bad Taste was going to be. And even if I wasn’t then quite up to getting the AIDS joke (and if you didn’t get it just now, don’t feel too bad) there were still enough showering sheep intestines, chainsaw-ed alien, and vomit stew splattered over the screen to keep us laughing along. I wish I could say we were plucky enough to be laughing along with beers in our mitts, but we weren’t. Neil’s parents were in the next room.

Bad Taste really is a truly amazing achievement and was filmed by Jackson, with unlimited invention, for a zero budget over a four year period. Apparently, a member of the cast turned up for the first day of filming unshaved and had to keep his unruly stubble for the next four years, lest he ruin continuity. Jackson would later manage to top even the gore on display here with the equally outrageous Braindead (which Channel 4 brilliantly showed on Christmas night 2001, and which my auntie politely insisted I keep watching during our Christmas family get-together despite the fact she was completely repulsed), but Bad Taste will forever have a special place in my affections for bringing oozing brains to BBC2.

Â

The Devils (1971)Â

Two nights after Bad Taste, the Forbidden Weekend cranked up the shock value yet further with this dizzying and debauched vision of religious hysteria from the depraved mind of Ken Russell. Having had something of a religious upbringing myself, I’ve always been susceptible to a bit of holy terror, but The Devils was the most mind-bogglingly blasphemous thing I’d ever seen. Or at least, I thought it was.

Based on Aldous Huxley’s novel The Devils of Loudon (no, I’ve not read that one either) The Devils takes place in the walled city of Loudon in medieval France, where the plague rages within and without, and randy but well-meaning priest Oliver Reed (turning in his greatest ever performance) has just taken over as governor. Reed is so randy in fact, that he secretly marries a lady, which, of course, priests are not supposed to do. Unfortunately for him he is the secret love of crazed nun Vanessa Redgrave, and when she catches wind of his forbidden nuptials all hell breaks loose. Redgrave is soon telling anyone that’ll listen that Reed is an agent of the devil, and is bewitching all the nuns and whipping them up into a sexual frenzy. Before Ollie can clear his name, an outrageously glam exorcist, who appears to have warped in from Russell’s later rock opera Tommy, arrives and actually does manage to whip the nuns into a frenzy, laying the blame firmly on our hero. He is soon the victim in a sickeningly brutal torture scene, and I hope I’m not giving too much away by revealing that the last time we see Oliver Reed onscreen in the film he is little more than a charred bone being used half-heartedly as a masturbatory tool by a now completely raving Vanessa Redgrave.

Watching The Devils for the first time is a truly unforgettable experience. I had already seen two Ken Russell films by this point, the aforementioned Tommy and his uneven but occasionally effective Mary Shelley biopic Gothic, but neither of those films could have prepared me for the full-on barrage of Ken Russell-ness that is The Devils. Redgrave and her visions of lovemaking with Reed as Christ, involving her kissing his stigmata, was the most shocking thing I had ever seen, but only until the exorcism scene, an expertly orchestrated orgy of unspeakable depravity as nuns rip off their habits and are forced into sadistically administered enemas left, right and centre. Little did I know at the time, however, that an even more startling version of this scene, in which the nuns rabidly molest a statue of Christ whilst a watching priest masturbates, had been forcibly removed and has yet to be reinstated into the film.

But for all this shock and torture, The Devils is also a very beautiful film in places, with a considered and heartfelt spiritual message. A practising Catholic himself, Russell’s film is a call for virtue and serenity in the face of fever and hysteria, and an essay on how political powers can use such hysteria to their own ends. It is his finest film, and there are many to choose from (ignore his innumerable critics), and it’s also, perhaps more easily, the jewel in the crown of Oliver Reed’s more-chequered-than-a-Croatia-kit career. Also noteworthy are the spectacular sets by Derek Jarman, who eschews the typical, muddied medieval look to create a clinical, blinding bright white fortress that haunts the mind much like something witnessed in a real religious vision.

(NB: The Forbidden Weekend was just one of many fantastic film seasons that both BBC2 and Channel 4 ran throughout the decade. In addition to Bad Taste and The Devils; Beat Girl, Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, The Night Porter, Bergman’s The Silence, and our old friend Performance were also screened. The weekend also boasted a superb two-part documentary on British film censorship in its pomp, Empire of the Censors, which makes for very interesting viewing today)

Â

El Topo (1970)

Two years later and BBC2 were at it again with another season of “forbidden” films, this time going under the name of the, erm, Forbidden Season. A quality line-up again, featuring something of an unofficial handover of Moviedrome presenters with Alex Cox introducing blood-splattered spaghetti western Django (featuring cinema’s second most famous ear removing scene) one week, and his replacement Mark Cousins presenting the spooky, majestic Gallic proto-slasher Eyes Without A Face the next.

The next film up was one that I had never heard of before, but was greatly anticipating as, by all accounts, it was to be the strangest film I would ever get the chance to lay my eyes on. El Topo, or “The Mole” in English, is a western, although not of the spaghetti variety, like the aforementioned Django, but of an altogether more distinctive, and rather troubling, flavour. The story begins, suitably enough for a western, with a black clad, silent gunslinger moseying on into a deserted town in the aftermath of a bloody massacre. And that’s the last easily decipherable thing that happens in the film. The remaining two hours are a freewheeling epic shambles in which our hero, who happens to be the El Topo of the title, first defeats the perpetrators of said massacre in the most bizarrely staged showdown you’ll have ever seen (one of his enemies finds time to create an Art Attack style tableau of a nude lady out of gravel, and then proceeds to writhe around on top of it), before heading out to test his mettle against four master gunfighters in a series of even more bizarrely staged showdowns. First he takes on a blind man, who for some reason has the voice of a woman, and whose only friend is a man with no legs astride a man with no arms (El Topo is not for the squeamish). He then takes on a really strong gypsy, who lives with his mum and a lion, a rabbit farmer who shoots crows, and an old man with a butterfly net. After he’s managed all this he only goes and gets himself shot to pieces by a woman with the voice of a man (a riff on an old favourite, it would seem), before he finds himself nursed back to health in a cave by an unruly rabble of cripples and deformed outcasts. And that’s just part one!

The second half of the film is stranger if anything, and sees the regenerated El Topo attempt to make his way in a corrupt western town full of cruel cultists and sadistic deviants, who at one point force him to have sexual intercourse with a dwarf before a baying crowd (El Topo is definitely not for the squeamish). But as any gunslinger worth his salt would, El Topo soon swears vengeance for the sins of this surreal Sodom, and the film mounts towards a fiery and suitably Biblical climax. “What it all means isn’t exactly clear, but you won’t forget it” as the tagline helpfully puts it.

I am willing to wager that El Topo remains to this day the strangest film ever shown on terrestrial television. It certainly remains the strangest film I have ever seen, and I seriously doubt anything will ever top it, or indeed Topo it, in terms of strangeness. I have come to see El Topo as something of a secret handshake amongst cult film fans, and no one who has seen it has failed to be mesmerised by it. That is not to say it is a perfect film, however. As already determined several scenes will not sit well with many (there is another particularly upsetting sequence involving a small child and a game of Russian roulette), and while I supposed it had to be deeply profound as a 15-year-old, much of the film’s philosophy appears to me today as decidedly cod. Somewhat fit to burst with symbolism, surrealism, imagery and iconography, El Topo aims in many directions, and never really nails one satisfyingly. For all that, though, it is still brilliant, and its brilliance lies in the mind of its director and star.

Â

Alejandro Jodorowski, the son of Russian immigrants to Chile, began his career as a mime artist and studied under Marcel Marceau, no less. In addition to mime, actor, writer and director, the great man can also add amateur scholar in comparative religion, playwright, composer, comic book writer, tarot reader, historian and psychotherapist to his CV. While he is, in my eyes anyway, the cult film fan’s cult film director, his career trajectory has put him in close contact with celebrity on several occasions. Not only was John Lennon a massive fan of El Topo, he also bankrolled Jodorowski’s next film, the slightly less surreal (although only slightly) mystic fable Holy Mountain, although fellow Beatle and El Topo fan George Harrison chickened out of a starring role. The sounds effects specialist from that film, Gonzalo Gavira, was later recruited by William Friedkin for The Exorcist on the strength of a single screening. Jodorowski then turned his attention to what was to be the first big screen adaptation of Frank Herbert’s fantastical sci-fi tome Dune. The provisional cast alone is an idiosyncratic wonder to behold, with the film set to star Orson Wells, Mick Jagger, Alain Delon, Geraldine Chaplin and Salvador Dali (yes, Salvador Dali). Pink Floyd were penciled in to do the music, and future Alien creator Dan O’Bannon was to co-write (Jodorowski had loved John Carpenter’s Dark Star, which O’Bannon also wrote and starred in). The Alien connection does not end there as H.R. Giger was on hand as art director, and some of his designs for Jodorowski were later used in the Alien trilogy. And if that weren’t enough, some of the set design too ended up in Star Wars, for, alas, this project was too leaden with mercurial talent to ever get off the ground, and Jodorowski finally buried his dream of filming Dune after David Lynch’s version got the green light some years later. His woes would not end there, either, with the copyright of both El Topo and Holy Mountain callously guarded by John Lennon’s notoriously tyrannical manager Allen Klein, depriving them of a video or DVD release until last year. Those two spectaculars aside, his first film Fando y Lis, following the adventures of a man and his paraplegic girlfriend, is easy-ish to find and worth watching (typically, its 1968 premier was followed by a full-scale riot) and his 1978 children’s feature (if you can imagine such a thing) Tusk is near impossible to find and not half as bad as most people make out (it also boasts a storming prog soundtrack). His most recent film of note is the surrealist horror masterpiece Santa Sangre (co-written with Dario Argento’s younger brother, Claudio), and these days he has an ever-changing list of works continually in progress (including an El Topo sequel), none of which have seen the light of day, and most of which have Jodorowsky disciple Marilyn Manson attached in some capacity. Like Ken Russell, Jodorowsky is a maverick, a genius, a wizard, and a true star. And also like Ken Russell, he is continually neglected by a staid modern film industry that just can’t handle him.

Â

Â

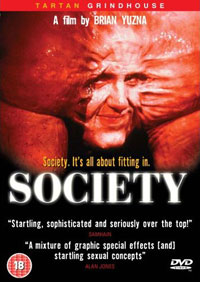

Society (1989)

Later in 1997 Moviedrome returned, and, as mentioned above, it had a new presenter, Mark Cousins. When most people talk about Moviedrome, they mainly refer to the Alex Cox era, but I can’t help but prefer Cousin’s reign and this is probably for two reasons. Firstly, the poetic film boffin was an Ulsterman, as am I, and still living in Northern Ireland at the time seeing a fellow countryman wax lyrical on the BBC’s cult film showcase somehow felt quite special. Secondly, I missed much of Cox’s run because I was too bloody young at the time, whereas I almost always watched with Cousins and saw a sequence of longstanding favorites there for the first time, including Society (the ending of which, I am about to give away).

I can recall hearing Quentin Tarantino in an interview once bemoaning the fact that no matter how well received and critically acclaimed Reservoir Dogs was, it would forever be known to the majority of people as “the film where the guy gets his ear cut off”. Well, for me, and everyone else I know who’s ever seen it, Society will forever be known as “the film where the guy gets turned inside-out after someone reaches their hand all the way down his throat and pulls his asshole out of his mouth”. That’s not to say that Society has nothing else going for it, it’s actually pretty brilliant throughout, you’ve just got to admit that as finales go, that certainly is memorable. I still can’t believe it went out on BBC2 on a Sunday evening.

Society is a gore-heavy horror satire about all-American rich kid Bill Whitney (Baywatch star Billy Warlock. Not that I ever watched Baywatch, you understand) who has it all, but still doesn’t feel like he fits in and suspects that things may not be as they seem. His fears seem to be confirmed when his sister’s ex-boyfriend gives him a tape of the other Whitney’s apparently indulging in a murderous orgy, and Bill seeks help. Before he can get it, however, the tape is wiped and his sister’s ex turns up dead under very suspicious circumstances. Bill then turns teenage sleuth and finally unmasks the truth; the entire upper class world he is a part of is peopled by a breed of evil mutants, his own family included, who feast on the living flesh of the poor in a disgusting orgiastic feeding frenzy. Understandably stunned, Bill must act fast if he is avoid being next on the menu, but luckily for him some inventive improvisation is enough to leave his predatory foe feeling rather “exposed”. Â

It still surprises me that Society is not more famous than it is, balancing several stomach-churning set pieces (with effects by the legendary Screaming Mad George) with lashings of black comedy. Its underlying message (the rich feed off the poor in society) is not conveyed with particular subtlety, but it’s true gosh darn it, especially in America. Perhaps one of the reasons it is not more widely regarded is that director Brian Yuzna never followed this, his debut feature, up with anything noteworthy. Despite having directed a true horror classic, Yuzna has spent his career turning out sequels for other horror films, having done two sequels for another classic, Re-Animator (2 and 3), and one apiece for two not-so classics Silent Night, Deadly Night (4) and Return of the Living Dead (3).

Whatever the reason, nothing can change the fact that Society goes further, hits harder, and, let’s face it, reaches the places that modern horror films just can’t (or probably just don’t want to) reach.

So there you have it, six films I saw on television many years ago when I couldn’t quite believe what I was seeing. I couldn’t quite believe how weird they were, nor could I believe how good they were. I’m sure everyone has memories of illicit film-watching when they were younger, and I’m definitely sure there are many people who remember Moviedrome as fondly as I do. It wasn’t intentional that all the films on this list were shown on BBC2, it’s just that this six for some reason loom largest in my mind. Channel 4 too was guaranteed to show fantastic films regularly, and, even if it never had a long-running Moviedrome equivalent, it did play host to as many groundbreaking seasons as BBC2 (notably the late 90s Extreme Season, with Mark Kermode). It also had it’s now sadly defunct 4 Later late-night strand (it was much better than Big Brother Live, and I like BB, but does it need to be on all night?), which occasionally played interesting films alongside it’s mix of lo-fi, lowbrow programming (film fans may remember the boisterous video review show Vids presented by two men destined to be known forever as ”the Welsh one” and “the Scottish one”). Even BBC1 chipped in with a great film or two every now and then. I remember they used to run 60s/70s mainstream classics midweek from time to time which was sometimes good (They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?, The Sting) and sometimes really, really, really good (Midnight Cowboy, Marathon Man). ITV (or UTV, as it was for me) was never, ever good, though. Even Channel 5 was better for films than ITV when it first arrived, and no, I don’t mean Confessions of a Window Cleaner.

I suppose all this nostalgia is born of the sad fact they really don’t seem to show decent films on terrestrial TV at all anymore. The accepted logic, of course, is that since the advent of widespread multi-channel television, the channels solely dedicated to films have reduced the need for films to be broadcast on the main five channels. I don’t buy into this, however, because as far as I can see the satellite channels rarely show anything worth bothering with either. Sickeningly self-referential, Film Four used to be interesting, but is now absolutely appalling (although they did show Peter Fonda’s melancholy western The Hired Hand recently, making a nice change from Dodgeball). Among the other channels TCM, Movies4Men (seriously, it’s good), and Zone Horror stand out, but you’re going to need to swell Sky TV’s coffers considerably before you can get hold of those.

Of course, you can pretty much get hold of anything you like on DVD now, but nothing can beat the feeling of catching an amazing film you’ve never heard of before on TV by complete chance, and that’s what Moviedrome was all about. Mark Cousins said in an interview not so long ago that he would love to present another series of Moviedrome, but the BBC either can’t or won’t stump up the cash needed required for the screening rights for films worth showing. This enforced absence is a shame on the BBC, and I for one can’t help but wonder about what great films I’ve missed out on of because of it.Â

The first film I can remember seeing on Moviedrome, going out on a Sunday night, and a red hot topic of conversation at school the following day. A film of two halves bleeding into each other, much in the manner of the sort of conscious shattering acid trip indulged in throughout, this was strong, heady stuff indeed.

Follow this link for a list of the world’s greatest movies.

The first half sees vicious East End thug James Fox, dishing out both crime and punishment with malevolent glee on his rounds. Fox enjoys his work a little too much and eventually comes a cropper with his crooked cohorts who then subject him to a disturbingly kinky beating. Needing to flee, Fox manages to wangle a room in the townhouse of faded pop star Mick Jagger (easily his best performance in a film career that makes David Bowie look like Burt Lancaster, but then, he is basically playing himself) who proceeds to lay on the psychedelic drugs and lets the mind-bending mind games begin.

Perhaps the thing that was most startling to me and my schoolmates about Performance was that it starred Mick Jagger. Watching this a few years before I became fully aware of the Satanic Majesty of The Rolling Stones, he was just another old pop star that my parents might have liked. Like Cliff Richard or something. Yet here he was cavorting with two naked ladies at the same time (one of whom was bandmate Keith Richards’ real life girlfriend, Anita Pallenberg) and taking weird and frightening psychologically damaging drugs with a psychotic criminal. Imagine Cliff Richard doing that. And if that wasn’t terrifying enough, who is that weird child woman that lives in his house? Why is his house so horrible and messy? Why is he singing to all those naked gangsters naked? Is that a bloke with a real Chelsea Smile? And, most importantly, what the hell happened at the end?

I must have been about 11 when Performance was on Moviedrome, but I remember it very clearly. I remember Alex Cox doing his introduction sat on a pool table, although I couldn’t have known who he was at the time. I should say at this point that as much as I like Cox as a broadcaster, and admire him as a filmmaker, I’ve never really warmed to any of his films. Having said that, I’ve only seen Repo Man and Sid & Nancy (both too arch if you ask me); there’s every chance that I might like one of his other films. But I digress…

I sought out Performance sometime later, of course, when I could truly appreciate it for the masterpiece it is. But catching it on late-night TV as a youngster was seemingly as crazy a trip as the one Jagger and co. go on in the movie and one that certainly whetted my appetite for more.

Â

Alligator (1980)