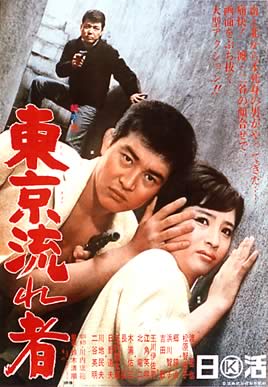

Film of the Day – Tokyo Drifter (Seijun Suzuki, 1966) | DaysAreNumbers

Seijun Suzuki is drinking in the Last Chance Saloon… Or rather, he is drinking in whatever the Japanese equivalent of the Last Chance Saloon is. The year is 1966, and Suzuki is the undisputed king of the B-movie in Japan. He is a contract director at the Nikkatsu Company’s studio in Tokyo, and he has already turned in a truly awe-inspiring 37 films in 11 years for his employers, many of which have had generous praise heaped on them by critics; most unusual for Japanese B-movies at the time. You’d think then that the suits at Nikkatsu would be pleased with their most prolific charge, but they’re not. You’d also think that they’d appreciate his films and the reputation-enhancing effect they have had on Nikkatsu, but they don’t. The trouble is that the top brass at the studio like their films to make sense, but Suzuki films, as brilliant, vibrant, and inspired as they may be, really don’t make that much sense at all. They certainly don’t make that much sense in a way that a promotion-conscious, profit-hungry producer cares about, at any rate. That’s why Nikkatsu have offered an ultamatium to Suzuki; tone down the craziness in your films or you’ll face the chop. He’s even had his usual, already relatively meagre, budget slashed for his forthcoming 38th film, just to ensure he has less finance to fund his inventive lunacy.

Film number 38 turns out to be Tokyo Drifter, and it probably won’t come as any surprise to you to learn that far from playing it straight, as requested, Seijun Suzuki actually turns in his most alluring, alarming, wild, wonderful and off-the-wall film yet. It’s also his very best film yet, but more on that in a minute. First, a bit of bio. Suzuki was born in Japan in 1923, and some twenty years later was recruited as a soldier for Imperial Japan, seeing action in the Second World War. Fighting in the Navy, Suzuki was twice shipwrecked, and once claimed in an interview that he found the horrors of war (which he’d witnessed first hand) rather ”comical”. It may well have been these experiences that informed the askew, and often unsettling, view of the world that he would later adopt in his films, and after the war he began work as an assistant director at the Schochiku Company’s main studio.

The young, promising Suzuki was poached by the rival Nikkatsu Company in 1954, and two years later our hero made his debut as a fully-fledged director in his own right with the pop star vehicle, Victory is Mine. The Japanese studio system at the time was as rigid and controlling as anything ever seen in Hollywood, and directors of B-movies were not given much time or money to spend on the films they were assigned to make. Suzuki soon worked out, however, that the low-budget films he was employed to make were so low down in Nikkatsu’s priorities that, provided he work cheaply and efficiently, he could quietly subvert them in ways that would at least grant him creative satisfaction, if nothing else. Thus he began to eschew the safe, formulaic approach generally taken to B-movie making in favour of more distinctive and daring methods of cinematic storytelling. Much of Suzuki’s initial, late 50s output is riveting, and already touched by oddball brilliance (for an example, see his earliest effort currently available, 1958’s Underworld Beauty), but the director himself credits The Bastard, made in 1963, as the true beginning of his career as a wayward auteur. Indeed, this is the point where the critics sit up and take notice of Suzuki’s rapidly developing idiosyncratic style. The Nikkatsu Company, on the other hand, fail to notice weirdness is afoot in their B-movie department until Suzuki releases Tattooed Life in 1965, after which he is reprimanded for the first time. In true Suzuki style he follows this with the even stranger, not to mention raunchier, Carmen from Kawachi, the following year, which equally displeases the studio. That’s two strikes against Suzuki, another and he’s out… The scene was set for Tokyo Drifter.

On the surface of it Tokyo Drifter is just another yakuza film, a hugely popular Japanese genre, highly similar to film noir, depicting the dangerous and action packed lives of the country’s criminal element. The plot of Tokyo Drifter is fairly run-of-the-mill for a film of it’s kind, albeit with some nice existential touches, and sees gangster Tetsu, determined to stay faithful to his boss, endangering his life by refusing to join a rival clan. When it becomes apparent that this decision may have put his boss in jeoprady too, Tetsu agrees to make himself scarce, and becomes the Tokyo Drifter of the title, wandering all over Japan. This doesn’t mean he’s out of harm’s way completely, of course, and he encounters many foes on his travels, before learning of a double cross that takes him back to the capital swearing revenge.

Exciting stuff but, as with Frank Carson, it’s the way Suzuki tells ‘em. As already noted, Tokyo Drifter was the director’s boldest concoction yet, and it really has to be seen to be believed. An intoxicating mix of colours, filters, lighting, and set design, the film has a rich and unwieldly aesthetic tone that must have been positively mind-blowing in the conservative Japan of the mid 60s. And it’s not just the madcap manner in which Suzuki paints a visual picture that makes the film so unique, he also proved something of a maverick behind the editing suite, too. I’m sure some of you are familiar with the old Godard adage that a scene which follows another scene in a film doesn’t necessarily have to be the scene that follows it, in other words the correct scene, narratively speaking. This description could well be applied to many of Suzuki’s films, too, particularly Tokyo Drifter. There are times when we think we’re right in the middle of the action, only for the camera to take us somewhere else altogether. Sequences are left unfinished and time jumps around illogically, but it’s all part of the reckless fun. Suzuki also shows scant regard for genre convention, either, and chooses to liberally sprinkle slapstick, sight-gags, running jokes, and even a handful of musical numbers all over this hard-boiled yakuza film. In no way imaginable was Tokyo Drifter the sort of thing an audience could have expected.

Despite the fact they should maybe have known better, it wasn’t the sort of thing the Nikkatsu company were expecting either. After hitting his paymasters with his most brazenly bonkers film to date, Suzuki predictably found himself called into the headmasters office once more. Despite the fact they already threatened him with the sack, they couldn’t ignore the ongoing support being shown for the director by the critics, and fiercely loyal cult following he was developing among Japanese students. Part of what had upset Nikkatsu most about the film was it’s vivid, retina-scorching use of colour, which they considered to be lurid, garish and unneccessary. So a compromise was reached, Suzuki could keep his job, but his next film had to be in black and white. Oh, and it really, really, really had to make sense this time. Or else he really would lose his job, and this time they meant it.

What did Seijun Suzuki do next? Did he turn in a pedestrian crowd-pleaser that proved a box office smash and made all his enemies at Nikkatsu rich and happy? Or did he make a film even madder and more magnificent than Tokyo Drifter, and pay the ultimate price professionally as a result? Tune in next week to find out!

I know you’re all dying to find out what happens next, but in the meantime please enjoy this typically head-spinning clip from Tokyo Drifter. Observe how Suzuki takes leave of the beginnings of a violent battle to showcase the main protagonist intoning a rather brilliant moody ballad, before returning to said battle just in time for it’s bloody climax. The man’s a true genius!