Film of the Day – The Naked Kiss (Samuel Fuller, 1964) | DaysAreNumbers

When I think of a classic “movie director” type, I always think of Samuel Fuller. While hardly wanting for favourable critical attention (not when you can count the likes of Scorsese and Tarantino as fans), it’s a bit of a wonder that Fuller isn’t more widely known. In an age when the vast majority of film directors are little more than clipboard-welding, rigidly careerist hacks, one can’t help but look back to the likes of Samuel Fuller for a bit of colour.

A bona fide grizzled, cigar-chomping tough guy movie maker, Fuller was also a highly-decorated Second World War veteran, and a no-nonsense intellectual, to boot (he pops up in a cameo role in Jean-Luc Godard’s masterpiece Pierrot le fou). And if the man himself was a vintage Hollywood type, albeit one with only minimal surface scratching required to reveal a deeper, more complex character, then that’s a description that can also be applied to his brilliant body of work. A director very much in the low-budget/B-movie/pulp cinema mould, Fuller would turn in just about every kind of genre picture beloved of the kind of stack ‘em high, sell ‘em cheap producers and minor movie moguls he was continually working under. From war films to westerns, film noir to melodrama, the great man’s oeuvre would be typical of countless other jobbing directors of his age were it not for the fact that, very much like the man himself, Fuller’s films boast raw guts and real brains in spades.

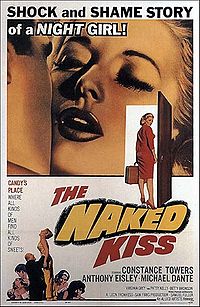

My personal favourite Samuel Fuller film is 1964’s The Naked Kiss, which is the last truly great film he would make for nearly 20 years, as his career would be cruelly put on hold by creative and financial difficulties throughout most of the 60s and all of the 70s. He certainly took his leave with a bang, though, and rather fittingly The Naked Kiss manages to pack everything that is great about Samuel Fuller into its edgy, economical punch. A bizarre, noir melodrama, you’re guaranteed to have never seen a film quite like The Naked Kiss, and at least two of its scenes will stay with you forever. Samuel Fuller always was a dab hand with an explosive, iconoclastic opening to a film (perhaps most famously juxtaposing the iconic Colombia Pictures logo with Beethoven’s 5th symphony at the start of his 1958 war drama, Verboten!), but the manner in which The Naked Kiss bursts onto the screen hands him perhaps his finest moment. The sort of red-hot swinging jazz that was still a byword for debauchery in the early 60s crazily parps away in the background as an enraged woman wildly beats a drunken man about the face with a boot. Suddenly the man leers forward, and pulls the woman’s hair off! She was wearing a wig and is completely bald! Simple, shocking, clever and reckless; welcome to the world of The Naked Kiss.

Our hairless heroine turns out to be prostitute Kelly, who was in the process of pulping her pimp when he pulled her wig off. It was him who shaved her hair off in the first place, and it’s that sort of treatment that’s causing Kelly to think about quitting the game. Undettered by being de-wigged, Kelly continues to savagely beat the bastard, and forcibly takes the money he owes her so she can start a new life in a small town. After a brief, steamy fling with local police chief Griff, Kelly decides to give up her old ways for good, showing just what a compassionate, capable lady she is by landing a job as a nurse at a children’s hospital. Griff isn’t keen on this, however, and he’s determined to run Kelly out of town, seeing her as nothing more than a no-good ex-prosi. Kelly also manages to make enemies at the local brothel (were they perhaps overly coyly refer to their employees as “bon-bons”!), as she makes it her business to dissuade young girls from taking the same sordid path she did.

She has no shortage of enemies then, but her sterling work as a top notch nurse has won her some admirers, too. Enter local aristocrat J. L. Grant (creepily played by character actor Michael Dante), who shocks everyone by announcing his intention to marry the former prostitute. Kelly gladly accepts, but her happiness is short-lived after she catches Grant attempting to molest a local youngster. The wealthy pervert pleads with her that she should understand as she too is a deviant, but something snaps inside Kelly and she strikes him dead where he stands. Imprisoned and at the mercy of Griff and other assorted enemies, Kelly must find a way to prove she killed Grant for his misdeeds and not his money, before time runs out.

If The Naked Kiss still seems steamy, provocative and downright weird today, imagine how it must have seemed in 1964! Samuel Fuller was a prize-winning reporter between the army and the movies, and his films have often been noted for their “tabloid” feel. This is not necessarily a criticism as, while they are often rather sensationalist (as The Naked Kiss undeniably is), they also boast a razor-sharp directness and a brutal sense of dark, dead-eyed logic. The combination of heated, intense storytelling and wild-card narrative antics, make the films of Samuel Fuller in general, and The Naked Kiss in particular, the most “alive” films of their era, and they are no less riveting today. Fuller also genuinely cares for his characters, and Kelly is the strongest, warmest, least sentamentalised female character in all of film noir, and possibly even melodrama, too (I can’t quite decide which genre The Naked Kiss truly belongs to). She is superbly played by Constance Towers, who went on to become a familiar face on US TV throughout the 80s and 90s.

The Naked Kiss is a true original from a true original and simply has to be seen. It is Samuel Fuller at the very top of his game, showing off with flair the dynamism, depth and humanity that have kept him held in such high regard to this day. His filmography is a veritable treasure trove of inventive low-budget, high quality filmmaking, beginning with the western I Shot Jesse James in 1949. Highlights from his 50s and 60s output are almost too numerable too mention, but his hymn to journalism, Park Row, a trailblazing racially sensitive western, Run of the Arrow, and the aforementioned, post-war Berlin based Verboten!, are all stone cold classics. After The Naked Kiss, arguably his masterpiece, Mexican financiers descimated his troubled acquatic actioner, 1969’s Shark!, in which Burt Reynolds starred and a crew member was tragically killed by a shark on camera. Fuller would be largely out of action until 1980’s stonking WWII memoir The Big Red One (tell your Star Wars-lovin’ friends it’s the best film Mark Hamill’s ever been in), which he would follow with the characteristically brutal, frank and highly controversially allegory for racism, White Dog (which Morricone did the soundtrack for, so more on that later). Samuel Fuller passed away, aged 85, in 1997.

One of the best ways to honour the man’s astounding talent is to kick back and enjoy the frenzied, jolting opening to The Naked Kiss.

Oh… and what was the other scene that will stay with you for the rest of your life? Well, Kelly sure is nice to those poor kids, but what the fuck is that creepy song all about?