(Not) Monday Morricone Madness!!! | DaysAreNumbers

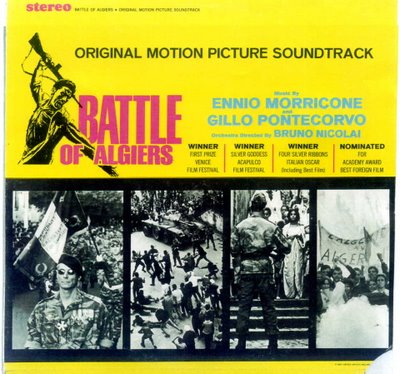

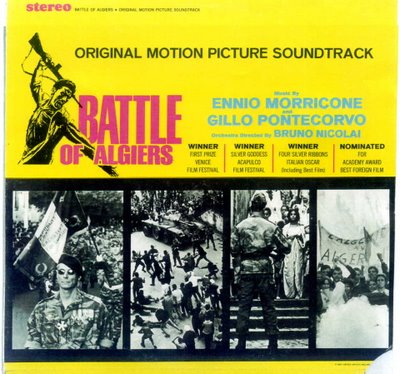

The Battle of Algiers (Gillo Pontecorvo, 1966)

There are two kinds of 100 Greatest Ever-type film lists, aren’t there? First of all, there are the ones voted for by the general public. These generally appear in magazines like Total Film or are broadcast in whopping 3 to 4 hour specials on Channel 4. The kind of lists that are ALWAYS topped by The Godfather or Star Wars, with The fucking Shawshank Redemption (seriously, why is it so popular?) and Jaws duking it out for bronze. Further on down, you’ll always get decent enough popular fare like The Terminator rubbing shoulders with classics like Citizen Kane or The Bicycle Thieves; films that the sort of people who vote in these things probably only feel like they should be voting for, and may not even like that much. Then you’ll always get something ridiculously recent and fluffy like, say, Mama Mia! sitting comfortably dozens of places above Rebel Without a Cause and Jules et Jim.

Of course, you should never ask the general public to vote for anything (The X Factor, general elections…), so much more interesting then, are the other breed of Greatest Ever Film-type lists; the ones voted for by critics and filmmakers themselves. These are a semi-regular feature in publications like Sight and Sound and Time Out, and until very recently, Citizen Kane ruled the roost apparently indefatigably. Latterly it seems to have lost it’s standing, and The Godfather (loved by everyone!), Vertigo and The Rules of The Game are now just as likely to be crowned top dog. Other staples of these high-brow countdowns include 8 1/2, Tokyo Story and The Battle of Algiers. It was on such lists that I first became aware of that last title, although I had already heard it’s mesmerising, militant title theme on countless Morricone compilations.

For a long, long time The Battle of Algiers was not an easy film to find, and despite universal critical approval, it wasn’t a film that many people really seemed to say anything about. A French-language film released in the mid-60s that didn’t belong to the Nouvelle Vague. An Italian Neo-Realist film released nearly 10 years after that movement had peaked. One thing was certain, however, The Battle of Algiers was a very controversial film, and had been banned in France for many years following it’s release. There were even some dark mutterings that it was even a film that promoted, supported and idealised terrorism.

When you actually get round to seeing it (which I did after tracking down the ultra-rare Tartan video release), you quickly realise that, far from idealising terrorism, The Battle of Algiers is (and I won’t say simply, as it is no mean feat) the most honest film about terrorism, it’s causes and effects, ever made. Chances are, it’ll remain the most honest film about terrorism ever made forever. There’s no better example of the absolute hash that filmmakers of any political-leaning or nationality can make of the subject of terrorism than to look at the slew of appallingly misguided films made about the situation in Northern Ireland. Even the recent German-made take on the wave of terror created by the Red Army Faction in the 70s and 80s, The Baader-Meinhoff Complex, was hopelessly cliched and off the mark. So what is it that makes The Battle of Algiers so good?

One of the main reasons it’s so popular with critics and filmmakers is that it’s both shot and staged to absolute perfection. With remarkable neutrality it tells the story of revolutionary cells emerging from the claustrophobic and impoverished environs of the Algiers Casbah quarter, during the last days of French rule in Algeria. Naturally enough, the European settlers fight back against this new wave of violence, which in turn provokes a greater response from the Algerian liberation movement. Very soon a crack team of French paratroopers, headed by the charismatic but ethically suspect Col. Mathieu, are called in to strike the final blow against the revolutionary movement. The film’s finale, and history itself, both serve to show however, that no matter who wins the battle of Algiers, the end result of the war is a foregone conclusion.

The genius of The Battle of Algiers is that it is unhysterical, unemotional and unbiased about the events that it depicts, and this coupled with director Gillo Pontecorvo’s previously acknowledged brilliantly shot, almost newsreel-like “action” sequences, makes it as close to being a documentary as a piece of fiction can be. It is, of course, closely based on actual events, and even stars one of the leaders of the real-life Algerian liberation movement, Saadi Yacef, loosely playing himself. Despite this level of cooperation with the Algerian side, Pontecorvo never expresses too much or too little sympathy for either party, with the actions of both being questioned. Even the aforementioned Col. Mathieu, despite using strong arm tactics such as torture to quash the terrorist violence, is not lazily portrayed as a villain. Rather, he is seen as a millitary professional simply trying to restore order in a desperate, and possibly hopeless, situation.

Algeria gained independance from France in 1962, and many other countries and causes came to see The Battle of Algiers as something of a testament to the success of that particular freedom movement. This was undoubtedly not the intention of those who made it, but the film would become notorious as a clarion call to arms in troubled times; with the global decolonisation process approaching fever pitch in the 1960s, The Battle of Algiers served as a raw reminder of the murky and painful death that imperialism was condemned to die. As already noted, the French government banned the film until the late-70s (never shy on banning films that touch a raw nerve, the French government; see also Stanley Kubrick’s Paths of Glory), but it would never lose it’s reputation as cinema’s last word on the use of violence, rightfully or wrongfully, in the struggle for freedom. As such, The Battle of Algiers rose again in the wake of 9/11 and the subsequent occupations of Afghanistan and Iraq. The Pentagon even invited top military brass to a private screening in 2003. Many in the English media would look to the film for both questions and answers following 7/7, as well, and there are now several high-quality DVD releases widely available.

The Battle of Algiers is more than just a political/historical artefact (no matter how relevant), and deserves to be chiefly remembered as a stellar piece of filmmaking. It is one of the few films that you can confidentally and unreservedly name as one of the greatest ever made as it is practically perfect and positively peerless; no wonder it’s on all them lists I was banging on about. Gillo Pontecorvo was not a director who could ever be described as prolific, he passed away in 2006, but his two other films of note are both worth seeing. His first film to garner international acclaim, Kapo, was a thoughtful depiction of life, and death, in a concentration camp. The film he would follow The Battle of Algiers with, Burn!, is suitably explosive and incendiary and, while not quite up to it’s predecessor’s standards, is vastly underrated and should be much more widely known. It also has an excellent Ennio Morricone soundtrack, and thus will feature in a future Morricone Monday. Speaking of which…

Hey, Aneet! Do you know the story about Pontecorvo going round Morricone’s house one day when they were working on The Battle of Algiers? The director was whistling a tune he had in mind for one of the main themes but, unbeknownst to him, Morricone was sitting on his balcony and heard him. By the time Gillo had got up to Ennio’s flat, Il Maestro was sat at the piano pretending that he had come up with the exact same tune! What a joker, that Morricone!

Ha Ha! Thank you Alan for a delightful story!

Asked several years ago if there were any other scores that gave him satisfaction during a period when his Western work was the focus of so much attention, Morricone offered some examples. “I have to cite the Battle of Algiers, which Gillo Pontecorvo directed in 1965. The musical score I composed for that movie was very simple”. Simple but also powerful and emotionally direct.