“Film star…” | DaysAreNumbers

“…propping up the bar, driving in a car, it looks so easy” Suede frontman Brett Anderson once warbled, and it’s not hard to see why he arrived at that conclusion. It would seem that, for the majority of the rock and pop elite, rocketing all the way up the charts (and all the way back down them again in Suede’s case, ouch!) just isn’t enough to sate those fragile/rampaging egos. So they start to look around for another way to get the love they crave and can’t help but notice those other preening and pampered posers, film stars. Then they think to themselves; “I could do that”.

Of course, back in the day when popular singers were commonly packaged as “entertainers” it was absolutely mandatory for them to take acting roles in motion pictures. Why, just look at the first man to ever talk in a film, mammy-loving Lithuanian and ”blackface” singer Al Jolson. Or rather, don’t look at him if you’re easily offended. Throughout the Golden Age of Hollywood, big name singers were big time stars, and it was simply unthinkable not to get them into the movies. I’ve always carried a strong personal distaste for the musical output of the so-called ”Rat Pack”, but I can’t deny that the main members each possessed more than a smidgem of acting talent, with Frank Sinatra in particular being a rather remarkable performer (most notably in The Man with the Golden Arm and The Manchurian Candidate).

Even those establishment threatenin’ rock ‘n’ rollers couldn’t resist the lure of the silver screen when they burst onto the scene with, most notoriously of all, Elvis Presley himself soon spending as much time acting as hip-swivelling (despite some occassionally pleasant and frothy results he would, of course, have been best advised to stick to the latter). Rock ‘n’ roll films became a genre unto themselves, and the cinemas were soon full to bursting with giddy teens literally ripping their seats up and hurling the debris at the screen to the sound of Bill Haley and the bleedin’ Comets playing Rock Around the Clock (actually the least exciting song ever written). Britain soon got in on the act, too, but our rockers were never going to be up to scratch (Tommy Steele! Cliff Richard!). Pure toe-tapping, adult-alienating fun was the raison d’etre for the rock ‘n’ roll film, although a few chart-topping heart-throbs of the era did display some not inconsiderable acting chops; witness Ricky Nelson’s fine supporting turn in the Western classic Rio Bravo, par example.

The bottom falls out of the whole rock/pop stars-appearing-in-films thing at some point in the mid-1960s, despite that decade getting off to a very good start. Under the inspired guiding hand of maverick American director Richard Lester, The Beatles showed everybody else how it should be done by starring in the genuinely great A Hard Day’s Night, and later Help! However, generally speaking, this new breed of beat group-based music bods were not quite charismatic enough, and by the end of the decade, far too twatted on drugs to really give acting in films a proper go. Some continued to have a bash, and many future top drawer directors cut their teeth on 60s pop films (John Boorman with The Dave Clarke Five, William Friedkin with Sonny & Cher, and Bob Rafelson with The Monkees, whom he also had a hand in “creating”, in the excellent Head). By the dawn of the 70s it was established fact that being a rock or pop star didn’t mean that you had to, or even wanted to, appear in films.

And so it continues to this day, though of course there are still a few singers and musicians who DO continue to appear in films. We all know about the obvious ones, and they are uniformly rubbish. Most only seem to have one good film in them, and it’s generally their first; be it Madonna (Desperately Seeking Susan), David Bowie (it’s The Man Who Fell to Earth, hush ironic Labyrinth fans), or Mick Jagger (Performance which is, like The Man Who Fell to Earth, directed by Nicolas Roeg who seemed to enjoy casting singers in his films; see also creepy Art Garfunkel having sex with a comatose Theresa Russell in Bad Timing, although you’ll wish you hadn’t). There are fewer still pop stars who are actually any good at acting, but notably both Cher and Bjork picked up well-deserved awards and critical plaudits for accomplished performances in two very different films (Moonstruck and Dancer in the Dark, respectively).

Today, however, we’re going to take a look at some of your favourite rock and pop stars appearing in films that you may have missed. I don’t think any of these films are overwhelmingly well-known, but some of the folks that appear in them are. So sit back, grab hold of that popcorn, or perhaps even them earplugs, and let’s see if Brett Anderson still reckons it’s all “so easy” after we get through this lot.

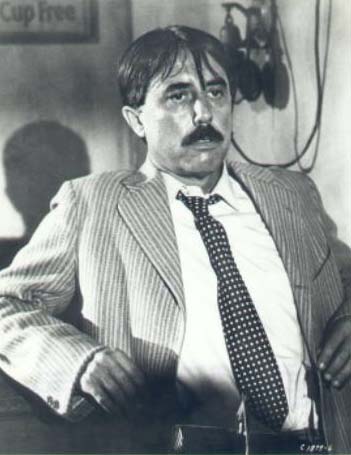

Charles Aznavour in Shoot the Piano Player (Francois Truffaut, 1960)

Charles who? You might have to ask your granny, but there can be no doubt that you have heard his most famous number, ‘She’ (covered by Elvis Costello on the Notting Hill soundtrack, to the speccy punk’s eternal shame). Aznavour is commonly referred to as the “French Sinatra” and, appropriately enough, he gives a performance worthy of Sinatra here.

In Shoot the Piano Player Aznavour plays Charlie, a one-time successful classical concert pianist, who has been reduced to playing at Parisian dive bars. Charlie also suffers from chronic shyness, and yearns to be able to catch the eye of a pretty barmaid. Unfortunately, just when things are starting to look up for Charlie and his potential new love, the musician’s gangster brother arrives on the scene and embroiles him in a heist job gone wrong. Charlie must then choose between his artistic and romantic ambitions and the loyalty he feels towards his family’s criminal element.

Shoot the Piano Player is an absolute corker (well, would you expect anything less from early Truffaut?), and you have to hand it to its director for coaxing out such an assured and low-key performance from such a major, glamorous star. It had been done one or two times before (again, see Sinatra in The Man with the Golden Arm et al), but Shoot the Piano Player makes it very clear to audiences that, just because it was a big singing star in the lead role, didn’t mean you were going to get a big musical number shoehorned into the action.

The zany rule-breakers of the French New Wave would often turn to singers to appear in their films, with other Gallic warblers including Chantal Goya, Johnny Hallyday and Jacques Dutronc turning up in films by Jean-Luc Godard and Claude Chabrol, amongst others. Indeed, many French New Wave stars – Brigitte Bardot, Anna Karina, Jean-Claude Brialy – would complete the cross-fertilisation by cutting records themselves. As for Charles Aznavour, again like Sinatra, he would go on to have a long and varied film career, and may also be familiar to UK audiences for his role in Volker Schlondorff’s clunky, yet undeniably haunting, fantasy allegory, The Tin Drum.

John Lennon in How I Won the War (Richard Lester, 1967)

As we all already know, Richard Lester helped The Beatles make the best pop films of the 60s with A Hard Day’s Night and Help! Both films are witty, fast-paced, colourful and knowing without ever being overly-ironic. Perhaps it was such a suitable marriage because, whether you like it or not, The Beatles pretty much define the decade they dominated, while Richard Lester himself could well be described as the most quintessentially ”60s” film director that there’s ever been.

Both Beatles films received much in the way of critical acclaim, and the confident performances of the four band members proved a pleasant surprise to many. In particular, warm, affable Ringo was singled out for praise, but it would be snickering, snidey John that Lester would cast in How I Won the War, a typically anarchic anti-war satire.

Not quite the lead, Lennon plays Gripweed, a private in the brigade of bungling Lieutenant Goodbody (appropriately played by future Frank Spencer, Michael Crawford). The film sees Goodbody and company embark on a sort of surreal version of the same journey taken by Samuel Fuller in his war memoir The Big Red One, as they begin in the deserts of North Africa and end up on the muddy banks of the Rhine. Along the way, the soldiers (played by a host of recognisable British acting talent, including Roy Kinnear, Jack MacGowran and Michael Horden) continually attempt to surreptiously bump off the dangerously inept Goodbody, but ultimately they all end up killing each other instead.

How I Won the War was not exactly given rave reviews on it’s release, and even proved controversial with it’s lampooning of certain aspects of the Second World War, a mere 20 years after the fact. It has justifiably been afforded a fairer reappraisal in recent years, but it is still a far from perfect film. It is too giddy and ridiculous to be a truly successful satire, and the cinematic gimmicks (the dead soldiers return as omnipresent ghosts, and Ethel from Eastenders pops up to comment on the film in a cinema at one point) come a little too thick and fast. There’s really not too much to say about Lennon’s performance, either, if you’ve seen A Hard Day’s Night then you’ll know what to expect, although he does visibly struggle in the more dramatic scenes. In conclusion, there were much better anti-war films to come (M*A*S*H, Kelly’s Heroes), and there are much better films in the oft-overlooked Lester canon (Juggernaut, Robin and Marian), but How I Won the War is still an enjoyable enough chuckle in the dark.

Later in 1967, The Beatles would make their penultimate collective foray into filmmaking with the occasionally inspired misfire, Magical Mystery Tour, tellingly made without Richard Lester’s assistance (the depressing break-up documentary, Let it Be, would mark the end of their career as a band). Following their split in 1970, each Beatle would take a different path in film and television, each one conveniently mirroring their solo musical output. Lennon, who branded acting “silly”, would pop up in numerous navel-gazing art films, before becoming the focus of a cloying and overly-sentimental feature-length documentary, Imagine. Paul McCartney went on to write and star in vacuous vanity project Give My Regards to Broad Street AND appear in the Comic Strip’s edgy and unbelievably dark Eat the Rich. Ringo Starr eventually became the much-loved voice of TV’s Thomas the Tank Engine, of course, but only after taking roles in some of the very worst films of the 60s and 70s (Candy, The Magic Christian, Caveman), although he did get to work with Ken Russell on the scarcely seen, utterly mental Lisztomania. Leave it to quiet, dependable George Harrison to turn in the best post-split work, however, with cameos in Beatles-spoof The Rutles and Monty Python’s Life of Brian, as well as being able to boast some truly impressive production credits, including The Long Good Friday, Mona Lisa, and Withnail & I. Good old George!

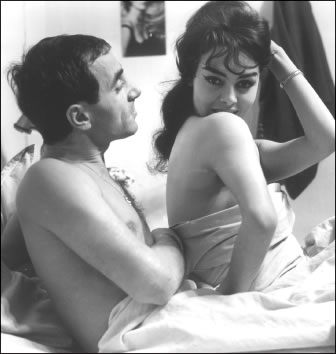

Serge Gainsbourg in Cannabis (Pierre Koralnik, 1970)

Sacre bleu, it’s Serge Gainsbourg! Yet although it’s always nice to say sacre bleu (and mon Dieu! and zoot alors!), it is not really all that surprising to find Serge acting in a film. Throughout his career everyone’s favourite dirty Frenchman (who was actually of Ukrainian origin) maintained a surprisingly busy second career as an actor, notching up a remarkable 47 credits in TV and film. He even managed to direct a few films of his own, with his 1976 effort, Je t’aime moi non plus (named after his naughty international smash hit from seven years before), marking his most successful stint behind the camera, and introducing the world at large to none other than Gerard Depardieu.

Gainsbourg made his acting debut in the fluffy, yet interesting, Brigitte Bardot vehicle/murder mystery Come Dance with Me, in 1959, and soon settled into a groove of appearing in just about any kind of B-movie being churned out in France throughout the 60s. Sword ‘n’ sandals epics, sex comedies, spy thrillers; he just about appeared in them all. 1963’s raunchy art film Strip-tease is noteworthy for not only starring future Velvets chanteuse Nico, but also for including an early version of Je t’aime with the German icon herself doing the heavy-breathing bits. Easily his best film work of the decade, however, was 1967’s made-for-TV Anna, a musical comedy starring Godard muse Anna Karina, and boasting a justifiably celebrated Serge-penned soundtrack.

He would return to the TV format with equally wonderful results in 1971’s Melody, but before that he starred in a feature-length crime thriller for Anna director Pierre Koralnik, with pretty disappointing results. I can’t really remember exactly what happens in Cannabis, and to be honest I can’t be bothered to watch it again. It is the sort of turgid late 60s/early 70s continental crime drama that goes so far out of it’s way to be raunchy and bloody and shocking, that it completely forgets to tell anything approaching a proper story while it’s doing so. Somehow, Koralnik had lost all of the breezy visual panache that he had brought to Anna, and it’s a real shame. Thankfully, the music Gainsbourg composed for the film is frankly incredible, with the pounding, guitar-heavy theme proving as good as anything else in his film oeuvre. This doesn’t mean that Serge himself is entirely blameless, however, as his acting is diabolical. Very charismatic and all that, and passable in the odd supporting role, but he really doesn’t have the chops to carry a whole film. Real life love Jane Birkin is equally unconvincing as the femme fatale, and the general grotty surreality of the whole affair is cranked up a notch by the appearance of cheeky Paul Nicholas (from Just Good Friends!) in a sizeable supporting role.

So yes, Serge’s biggest gift to the movies was his music, and several more of the horrific films he appeared in are also worth checking out for the soundtrack alone (particularly 1969’s Slogan, on the set of which he first met Jane Birkin). Either side of the majestic Melody, Gainsbourg would accept a supporting role in McCarthy witch-hunt victim Abraham Polonsky’s gentle period drama, Romance of a Horsethief, and later, begin filming the mysterious, highly controversial, never-going-to-be-released-ever, Jerry Lewis Holocaust comedy The Day the Clown Cried (the Holy Grail for fans of all films weird and wonderful, a fucking Jerry Lewis slapstick comedy about a clown who leads children into the gas chambers at Auschwitz!).

I’ve always thought of it as a bit of a shame that Gainsbourg never had a proper collaboration with any of the leading lights of the French New Wave, which was in full swing at exactly the same time he was making some of his best music. A Godard-Gainsbourg team up, for example, would have been an absolute dream combo, but it never came to be. The closest thing we’ve got is a Serge soundtrack for the impossible to find early 60s portmanteau picture The Beautiful Swindlers, which featured a segment directed by Godard and another by Claude Chabrol, but no one in the world has apparently ever seen it. Oh well, let’s light up a Gitane for Serge anyway, and pop on the Anna soundtrack while you’re at it.

Lee Hazlewood in The Moonshine War (Richard Quine, 1970)

“‘These Boots Are Made for Walkin” writer passes away aged 78″ read the headlines on all the obituary pages that Lee Hazlewood was lucky enough to make it on to in the wake of his death two years ago. Of course, that song is most probably the greatest Number One single of all time (up there with Serge’s Je t’aime, hey!), but for all of us hooked on unearthing the great man’s numerous classic, catchy and oddball albums, there is so much more to Lee Hazlewood than that.

A musical outlaw of near-mythical proportions, Hazlewood began his career as a producer, and sat behind the mixing desk on several whopping late 50s hits by guitar virtuoso Duane Eddy (it is rumoured in certain circles that Hazlewood was the man who taught Phil Spector how to produce, if that’s true it’s a shame he didn’t teach him how to not shoot people, too). Switching to the front of the mic, Hazlewood quickly established his unique brand of silly and saucy, yet always poignant, freewheeling mariachi and rockabilly-tinged country crooner toons. Impressed with the results, Frank Sinatra (that man again!) made our Lee an offer he couldn’t refuse; namely to produce a series of albums with Ol’ Blue Eyes’ daughter, Nancy. This would mark the beginning of the most high-profile chapter of Hazlewood’s career, as not only would he pen ‘These Boots Are Made for Walkin” for Nancy during this period, but together they would score a series of seminal kooky hits with glitzy, yet somehow still glib and sinister, duets including the legendary ’Some Velvet Morning’ (later almost tarnished forever by Primal pissing Scream and Kate cunting Moss).

Anyone who’s ever heard a Lee Hazlewood album may well be surprised that it took the singer so long to pursue some acting work, but it wasn’t until the hits with Nancy dried up in the early 70s that he chose to make his film debut (barring a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it cameo in Swingin’ Sixties romp The Sweet Ride, in 1968). Hazlewood occassionally showcased his rich, warm, and naturally deadpan speaking voice during bizarre, and often hilarious, spoken word segments on his albums. Listening to those recordings you might suppose that Lee Hazlewood would cut a rather fine and captivating figure on screen, and you’d be absolutely right. In fact, Lee Hazlewood’s performance is just about the best thing in The Moonshine War.

That’s not to say it’s a bad film, at least it’s certainly not as bad as Cannabis (the film, not the drug). The plot is basically a loose re-working of A Fistful of Dollars, with corrupt prohibition era G-Man Patrick McGoohan playing the hillbilly bootleggers off against a sadistic gang of gangsters in a boozy turfwar which lends the film it’s title. There are a few thrills and spills along the way, but you soon tire of the endless jalopy chases and the sight of men clad in dirty dungarees, scrambling desperately to put out burning barns. Nevertheless, there is some enjoyment to be had here, and an early highlight of the film sees Hazlewood, playing the henchman of the lead gangster, literally steal the shirt of someone’s back in a crowded diner. All drawl and mischievous menace, the singer even puts some of the acting pros in the film to shame; namely Alan Alda, who is horrendously miscast as the hillbilly hero. Sadly, they didn’t ask Hazlewood to compose any music for the film, and the soundtrack contains a handful of hilariously inappropriate contemporary soft pop numbers. Incidentally, journeyman director Richard Quine is also responsible for the film with the worst title ever concieved… Wait for it… Oh Dad, Poor Dad, Mama’s Hung in the Closet and I’m Feeling So Sad. Imagine asking if they have that in Blockbuster!

This was to be Lee Hazlewood’s first and last significant role in an American film, but he would continue his acting career elsewhere. One of life’s natural nomads, he subsequently uprooted and moved to Sweden, where he teamed up with Scandinavian exploitation hack, Torbjorn Axelman. This partnership would produce a series of odd, memorable films including an excellent TV special, Cowboy in Sweden, a weird slice of revolutionary hippie drama, Smoke (also starring They Call Her One Eye’s Christina Lindberg), and the perplexing, half documentary/half fantasy A House Safe From Tigers. Perhaps of most interest today is their concert film, Nancy & Lee in Las Vegas, but all of these films are sadly, desperately hard to find. Sort it out someone!

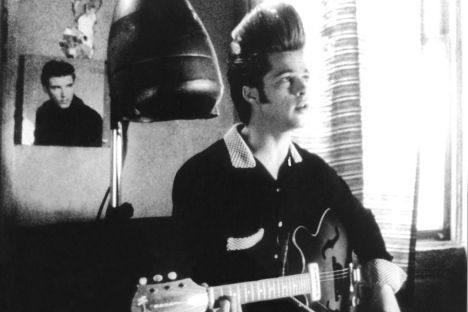

Richard Hell in Smithereens (Susan Seidelman, 1982)

Yeah maaan, punk’s here and you’d better get used to it! You could be forgiven for thinking that those angry punk rockers might have too gosh darn anarchic to consider slapping on the greasepaint for a bit of thespian work, but you’d be wrong! To be fair to them, it’s not like they were landing big roles in Hollywood blockbusters and indeed, on both sides of the Atlantic, an interesting new wave of independent cinema developed in the slipstream of punk.

This isn’t even the first film that proto-punk poet and Voidoids frontman Richard Hell appeared in! Prior to Smithereens, Hell appeared in the lo-fi punk docu-drama Final Reward, and even co-wrote and starred in his own feature length film, Blank Generation (I’m guessing he came up with the title), with former Fassbinder company player turned schlock auteur Ulli Lommel behind the camera and helping out on script duties. That is a pretty half-baked and ponderous film, however (despite a handful of blistering Voidoids performances), and one that certainly pales beside the quietly magnificent Smithereens.

Coming on like a punked up take on Fellini’s Nights of Cabiria crossed with a late 70s urban re-imagining of Ghost World, Smithereens is an appropriately zero-budget look at the life of Wren, a wannabe hipster/eternal loser trying to make a name for herself in the decrepit locales of post white flight New York. Whilst out one night shamelessly distributing posters of herself to uncaring subway passengers, she captures the attention of Paul, a bright-eyed out-of-towner currently living in the back of his camper van. Paul seems a little too “normal” and “nice” for Wren, however, and she soon finds herself much more interested in up-and-coming rock star Eric (guess who plays him), who promises to give her a start in the business. The trouble is, of course, that Eric is a fucking bastard, a liar, and a thief, but our heroine is so blindsided by his grubby charm that she just keeps on making the wrong decision. Very soon wild and frivolous Wren begins to come unstuck, especially after she burns her bridges with Paul, her flaky friends, and her fucked-up family.

Richard Hell is a perfect fit as preening punk rocker Eric, and as the film progresses it slowly dawns on you that he is an absolute dead ringer for a more rough around the edges James Woods. There’s some decent Voidoids stuff on the soundtrack too, but the choicest musical cuts in the film belong to The Feelies; THE great lost American new wave band. Smithereens itself is a great lost film, perhaps the greatest ever made about punk-era New York City in all it’s ragged glory, with a witty, gritty, and beautifully crafted cautionary tale at it’s core. It’s no surprise, based on the evidence here, that it’s writer and director went on to make one of the most popular hits of the 80s with her next film, Desperately Seeking Susan. Infinitely more surprising is that Susan Seidelman didn’t enjoy much success at all following that film (which starred another singer, of course, one slightly more famous than Richard Hell), with a handful of underperforming comedies (Making Mr. Right, Cookie, She-Devil) eventually relegating her to that cold, dark fate awaiting all female American directors of the 80s and 90s; guest-directing episodes of Sex and The City. Thankfully, her most recent film, Boynton Beach Club, performed well at the US box office, and attracted some deserved critical praise.

Meanwhile Woods-alike Richard Hell would make a more low-key appearance in Desperately Seeking Susan, but other than that he’s only notched up a few extended cameos in an assortment of low-budget festival-fillers. The bulk of his appearances onscreen these days are as a talking head in limitless punk documentaries, in which he routinely, and wrongfully, accuses The Sex Pistols and other British punk bands of lazily ripping him off. Speaking of whom…

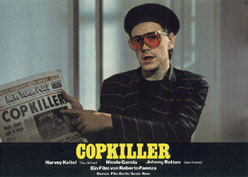

John Lydon in Copkiller (Roberto Faenza, 1983)

Yes, THAT John Lydon; AKA Johnny Rotten. Taking up the second half of our “punk pack” is one of Britain’s finest, but it wasn’t as easy for our leading snarlers to make it in the movies as it was for the Americans. In the 80s, for example, you wouldn’t bat an eyelid if you saw New York Doll David Johansen (Scrooged) or Blondie’s Debbie Harry (Hairspray) crop up in the odd mainstream comedy. Back in Blighty, however, the film roles were less forthcoming for the punk elite, unless you can bring yourself to expand your definition of punk to include Toyah and Sting.

The Sex Pistols did make their own sneer-y, nihilistic equivalent of the 60s pop film with The Great Rock ‘n’ Roll Swindle (as did The Clash, with Rude Boy), but for his dramatic debut the Artist Formerly Known as Rotten would have to decamp to the USA (albeit to appear in an Italian production). In Copkiller Lydon is Leo Smith, a young, disaffected New Yorker with a sarcastic London accent that not one single person questions throughout the film. He stars opposite Harvey Keitel, who plays Lt. Fred O’Connor, a crooked cop building a secret love nest with his partner (in both sense of the words), using cash pinched from the police service. O’Connor is one worried cop, not only is he engaged in a clandestine homosexual relationship and stealing police funds, but there is also a killer on the loose in New York. A killer who, you may have guessed from the title, exclusively kills cops. When Leo mysteriously turns up on O’Connor’s doorstep cryptically claiming to be that very killer, rather than risk having his hidden world exposed, the Lt. decides to hold Leo prisoner in his hideaway, and a psychological game of cat and mouse develops under these strange circumstances.

I’m surprised more people haven’t heard of Copkiller. I remember that when I first heard of it, I was surprised that I hadn’t heard of it (if that makes sense); a film starring John Lydon and Harvey Keitel… Why isn’t this more famous? Well, part of the trouble is that Copkiller isn’t very good. The above synopsis may well make it sound intriguing (even if do say so myself!), but in the end the film is so slovenly rendered that all that perverse potential is slowly, boringly bled out of it. What you get in the end is a sort of pedesterian play on Performance crossed with a tedious take on Cruising. The one redeeming feature of the whole affair is John Lydon’s performance. He is, in fact, so captivating that he actually makes the film worth sitting through. As noted earlier, he makes no effort to tone down his cockney twang, and his performance is essentially a housebound version of the Rotten persona, but would you want it any other way? Quiet and calculating Harvey Keitel can barely share the screen with him, and the whole shebang is barely watchable when Lydon isn’t in it.

The famously volatile singer never took another film role, sadly. I’m not saying he was a Brando in the making, or anything like that, but he certainly makes a superbly sinister impression in celluloid. Perhaps he could have played the Alan Rickman role in Die Hard? Something like that, anyway. It’s no surprise that he plays to the camera so well here, as Lydon was always a singer conscious of dramatic effect. Those of you who can remember the punk edition of the BBC’s fantastic popular music history from 1995, Dancing in the Street, may recall The Sex Pistols frontman claiming to have based Johnny Rotten’s malevolent stage swagger on Laurence Olivier’s explosive performance as the hunchback king in Richard III. Inspired!

John Lydon was initially asked to come up with the soundtrack for Copkiller, and fans of Public Image Limited will no doubt have heard the song ‘The Order of Death’. The title of that song was the film’s working title, but like the music Lydon wrote, it was never used. Instead, none other than Ennio Morricone was hired by director Robert Faenza (who is considered a bit of a wild card in Italy, but I’ve never seen anything else he’s done), but it says a lot about Copkiller on the whole that even the music of Il Maestro is uncharacteristically limp and unmemorable. No, this one really is for Lydon Fans Only, but then who doesn’t love Johnny Rotten?

Tom Waits in Down by Law (Jim Jarmusch, 1986)

You might recall that somewhere towards the beginning of this increasingly epic ramble, I referred to Nicolas Roeg’s tendency to cast musicians in his films. Well, if there’s one modern director whose taken a casting cue from the arty Englishman, it has to be Jim Jarmusch. The average Jarmusch film is chock-a-block with music talent in acting roles and indeed, his cult classic second film, 1984’s Stranger Than Paradise, features three instrument fiddlers in the lead roles; saxophonist and Lounge Lizard John Lurie, Hungarian chanteuse Eszter Balint, and former Sonic Youth drummer Richard Edson.

Down by Law is his third film, and while John Lurie returns, the most reknowned musical member of the cast this time round is Tom Waits. Waits plays Zack, a freshly-fired and possibly alcoholic radio DJ who, after being thrown out of his apartment by his irate girlfriend, committs a seemingly minor crime only to end up staring at a life sentence in a harsh Louisanna jail. His cellmate turns out to be Jack, a pathetically smalltime pimp who fell foul of police entrapment on the same night, and the pair initially bicker and argue with each other in the foul, enclosed atmosphere. This dynamic changes, however, with the introduction of Roberto (Life is Beautiful’s Roberto Benigni), a charming and naive Italian who believes he may have found a means of escape for the incarcerated threesome.

Tom Waits is easily the most accomplished actor on this list and, as with Lee Hazlewood, a quick listen to some of his records is enough to make it apparent why he is such a natural on the silver screen. As much of a crumpled beat poet as a traditional singer, and the proud owner of a wonderfully weather-beaten face and thick, smoky voice, Waits can add a hefty dose laconical cool to almost any film, and therefore he is a perfect fit for a Jarmusch production. Downbeat, dour, and deadpan, the director’s 80s oeuvre represents some of the finest independent filmmaking of it’s era. Suitably enough then, Down by Law is an askew delight; a jailbreak film were the emphasis is placed less on the escape (which we don’t even see), and more on Waits and Lurie’s resentful double act slowly thawing in the Louisanna swamplands were Roberto comes good and brings the grumpy crooks together. It is also beautifully photographed by frequent Jarmusch collaborator Robbie Muller (who also worked with Wim Wenders, a big influence on the American), and both Lurie and Waits add some killer cuts to the soundtrack.

Tom Waits has numerous film and TV credits to his name, and is always in demand as an actor. He made his debut in the Sylvester Stallone (!) directed Paradise Alley, and in addition to his work with Jim Jarmusch (he also pops up in the later Mystery Train and Coffee & Cigarettes), he has appeared in several films by Francis Ford Coppola. In particular, his performance in Coppola’s film of Bram Stoker’s Dracula (in which he plays Drac’s doomed disciple, Renfield) marks such an incredible transformation for the gravelly-voiced American that when I saw that film when I was a youngster, I thought it was Ben Elton! He really should have given Keanu Reeves some on-set accent lessons.

John Lurie, too, would continue to be offered work as an actor, and ended up appearing in several bona fide 80s classics (including Paris, Texas, Desperately Seeking Susan, and The Last Temptation of Christ), before long-term illness sadly restricted him to simply becoming a brilliant painter (you should also check out his hilarious early 90s TV show Fishing with John). Meanwhile, Jim Jarmusch is adding to the list of musicians that have appeared in his films to this day, a list that now includes, in addition to those already mentioned; Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, Joe Strummer, Iggy Pop, Gibby Haynes, The Wu-Tang Clan, and The White Stripes. Perhaps Jarmusch likes to work with musicians so much because he used to be one himself. His early 80s synth rock group, The Del-Byzanteens, are well worth checking out, although unfortunately their one album (Lies to Live By) has been out-of-print for many years now. Again… Someone sort this out, please!

(couldn’t find any pictures of Nick Cave in Johnny Suede, sadly, so here is one of Brad Pitt for all you ladies)

Nick Cave in Johnny Suede (Tom DiCillo, 1991)

One notable absentee from the list of musicians who have acted in Jim Jarmusch films is the director’s old mate Nick Cave. The pair both lived in West Berlin for a spell in the late 80s, and apparently had a great time going around together convincing strangers that they were twin brothers. This physical likeness was the basis for a near-legendary boys club formed by Jarmusch; The Sons of Lee Marvin. As the name may suggest, bearing a passing resembelance to the late tough guy actor is a pre-requesite for membership, and in addition to messrs Cave and Jarmusch other members are thought to include John Lurie, Tom Waits, Neil Young, Iggy Pop, and Sonic Youth’s Thurston Moore. I’d like to suggest that they ask recently sacked Charlton Athletic manager Alan Pardew to join, as he darn looks like Lee Marvin, too! Not sure how he’d fit in with the other lads, though. “Yes, Iggy, I was going to twat that Arsene Wenger, I tell you!”.

Ahem… Nick Cave has appeared in several films, despite this, and his most sizeable role came in a film directed by former Jarmusch DP, Tom DiCillo. Johnny Suede stars a then fast-rising Brad Pitt as the rockabilly-throwback hero whose stage name lends the film it’s title, and who is attempting to launch a music career in rundown downtown hipster New York, where all manner of sinister and surreal shannigans take place day and night. The struggling singer falls in with a spoilt rich girl, Darlette, who insists that her dysfunctional mother is an influential record executive who can put Johnny’s black suede shoes on the road to stardom. Like everyone else in town, Darlette idol worships low-rent, druggy rock star Freak Storm (Cave, of course!), and Johnny soon finds himself attempting to grease into his inner circle as well. All the while, however, our hero has been cultivating an awkward romance with Yvonne, a kindly, but painfully uncool, teacher at a school for the disabled. With time and money running out, Johnny contemplates settling down with Yvonne, but is his heart truly in it? And, furthermore, does she even want him?

Johnny Suede is a tragically overlooked and underrated film. Chiefly acknowledged as an early Pitt curio these days, it should really be regarded as one of the definitive American indies of the early 90s; up there with Reservoir Dogs and El Mariachi, in my opinion. Very much in the Smithereens mould, it is essential viewing for anyone who’s ever tried to be cool and failed dismally. It is also side-splittingly funny, and I defy anyone who claims to have a sense of humour to see this and not fall about laughing every time someone offers them some chicken thereafter. See it and you’ll understand. Nick Cave (who is integral to the “chicken” scene, incidentally) is marvellous in this film, and gamely sends up his own wildman reputation with relish. He also makes no attempt to conceal his broad Australian accent rendering the character of Freak Storm even more gleefully ludicrous.

Spunky Catherine Keener appears in an early role as Yvonne, and a host of other future indie faves make cameos as well, including a token turn from hard-working Samuel L. Jackson. Although I’ve never been a fan, I can’t deny Brad Pitt his due, either. The character of Johnny Suede was based on a stand-up routine performed by DiCillo himself, but Pitt brings the character brilliantly to life here, with a permanently bemused expression peering out from under a teetering, gargantuan quiff. In an interesting coda to the film, DiCillo’s equally pleasing follow-up, Living in Oblivion, would tell the story of a downtrodden indie director making his first feature while struggling to control a brash, obnoxious and deeply unpleasant blonde pretty boy star. DiCillo has always denied the character is supposed to be Pitt, but anyone who has seen Living in Oblivion possibly couldn’t help but two and two together. The director followed that up with the superb Box of Moonlight, and he still occassionally bobs to the surface with the odd interesting release (including 2006’s Delirious which featured another rocker, Elvis Costello), even if some of them have been condemned to a straight-to-video berth.

But, what of Nick Cave? Johnny Suede wasn’t his first film role, before that he had appeared as himself in Wim Wenders’ ponderous and overrated spiritual love story, Wings of Desire. He also played an inmate in the harrowing Aussie prison drama Ghosts… of the Civil Dead, which he co-wrote with director John Hillcoat. Cave and Hillcoat would re-team to write the well-received antipodean Western, The Proposition, in 2005. Another notable exploit as screenwriter for Cave was when not-quite compatriot Russell Crowe (he is, of course, a Kiwi… The nationality, not the fruit) requested the singer write a script for a potential Gladiator sequel. The Bad Seeds singer responded in kind and perversely dreamt up a scenario in which the Crowe character from the first film is resurrected in the future and heads off to fight in Vietnam! Sadly, it looks like this will never be made. Bringing things somewhat full-circle, Cave’s last appearance in a film was a cameo as a white blues singer in 2007’s The Assassination of Jesse James, which starred Johnny Suede himself, Brad Pitt.

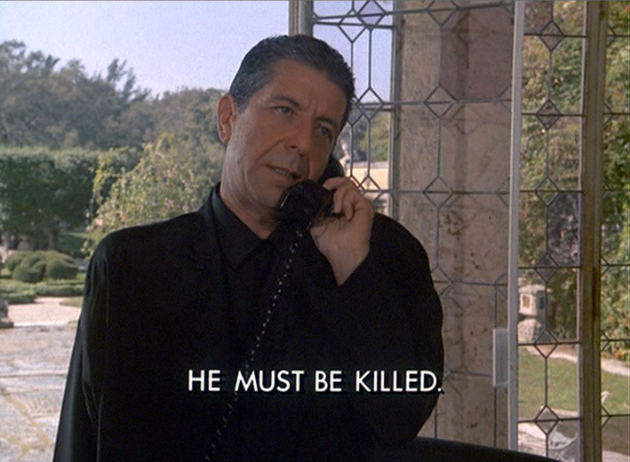

Honourable mention… Leonard Cohen in Miami Vice

Yes, you read that right! Leonard Cohen in Miami Vice! It’s the single most amazing trivia fact in my repertoire; maudlin troubadour Leonard Cohen once appeared in an episode of Miami Vice as the head of Interpol! Apparently, his son was a big fan of the show, or something like that. I was initially going to include this on the list, but decided not to as it is, of course, a TV show, and I had no shortage of films to write about (which I’m sure you’ve found out the hard way if you’ve read all this). Also, while it is hilarious in itself that LEONARD COHEN should appear in MIAMI VICE (he just sort of mumbles a lot in French), the episode itself, French Twist, is as overly flash, yet ultimately tedious, as every other episode of that over-hyped 80s monstrosity. So there!

Anyway, what have we learned from all of this? Basically, that sometimes musicians and singers act in films. Often with good results, mainly with terrible results, but it’s always cool and interesting when they do. In, fact I still wish it was par for the course for music people to make films, and I think every band should be forced to make a 60s/Monkees style pop romp at least once in their career. Hats off to Outkast for attempting to revive this tradition with 2006’s Idlewild, despite the fact that nobody went to see it, and those who did were scarred by the experience.

All the films above were selected because none of them are particularly well-known, and they all feature ”acts” whose music I enjoy. I really wanted to include obscure early 90s romcom Sweethearts as it features Pavement’s Stephen Malkmus, but alas I could not find a copy.

If there’s anything you think I’ve missed, or any favourite films of yours (starring music folk, of course) that you want to tell everyone about, please leave a comment… And don’t forget to rock on!